Goldmining in the Coromandel

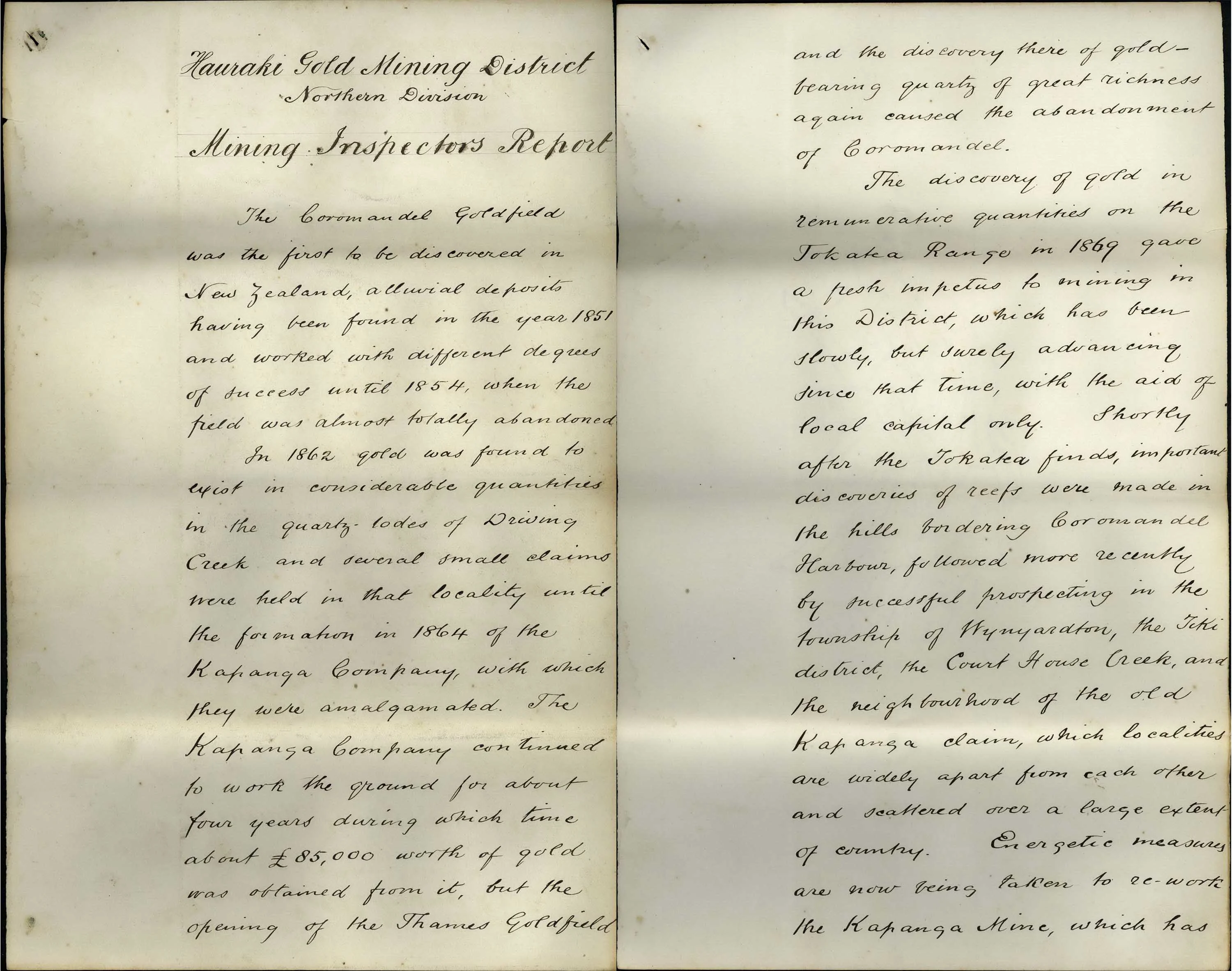

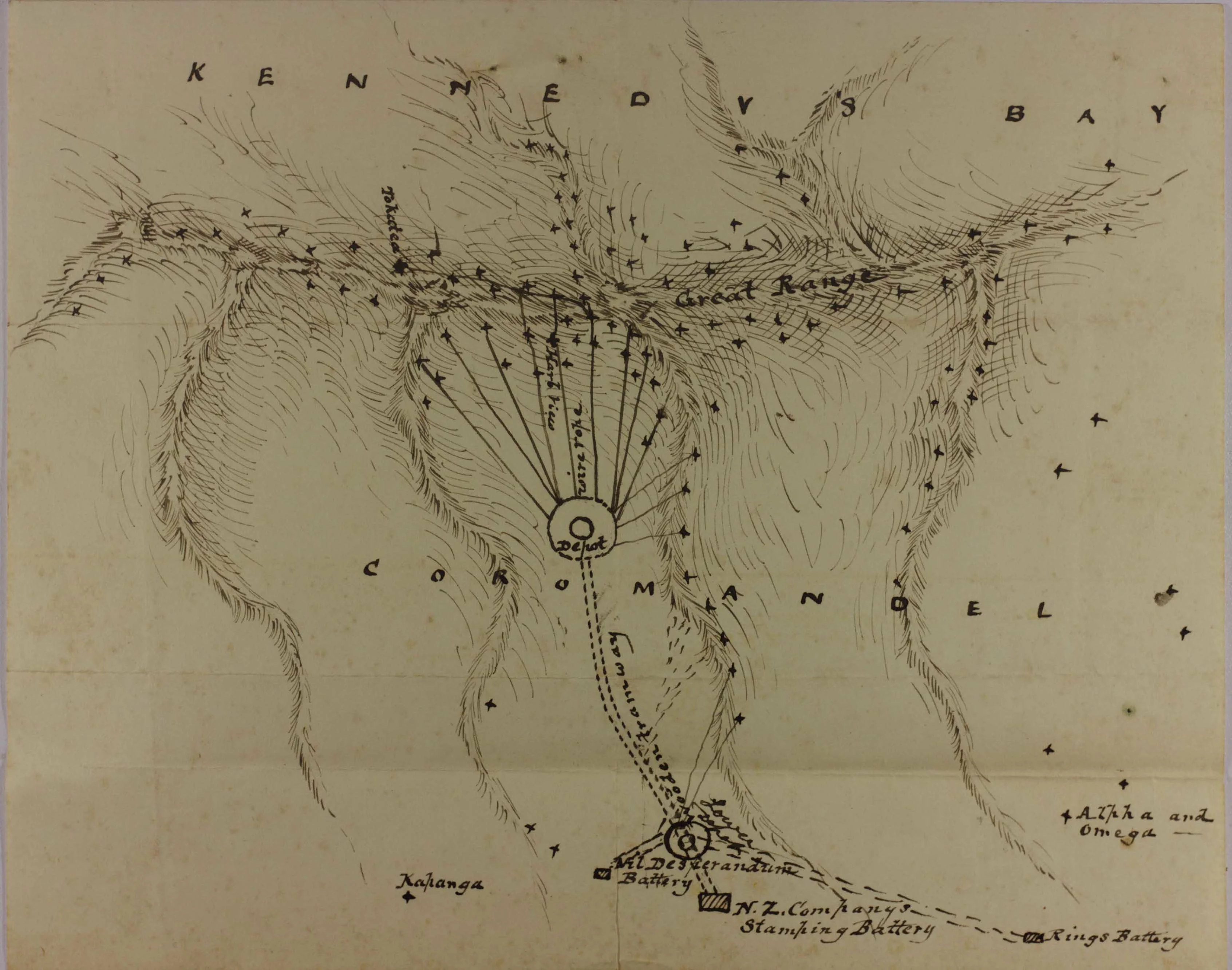

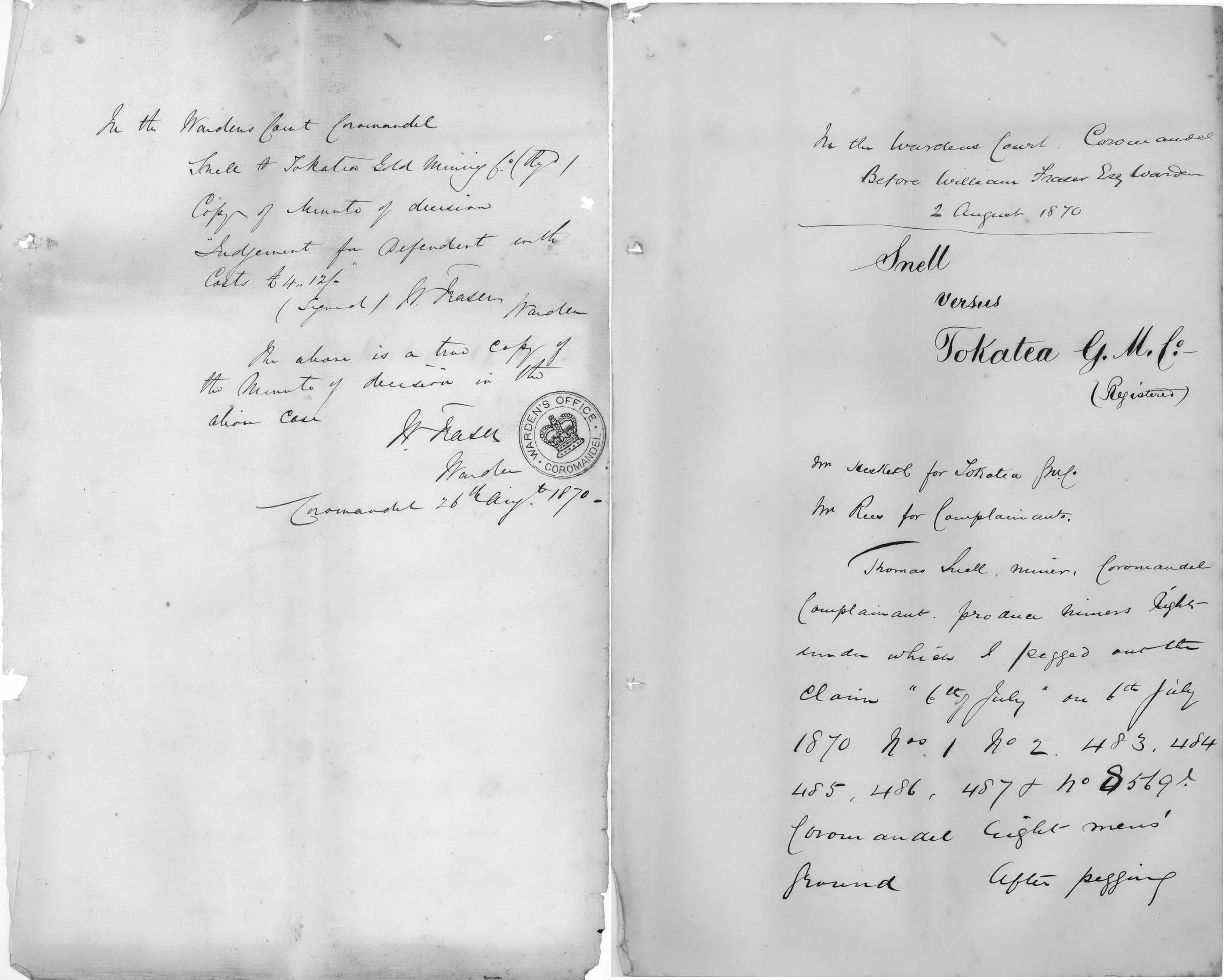

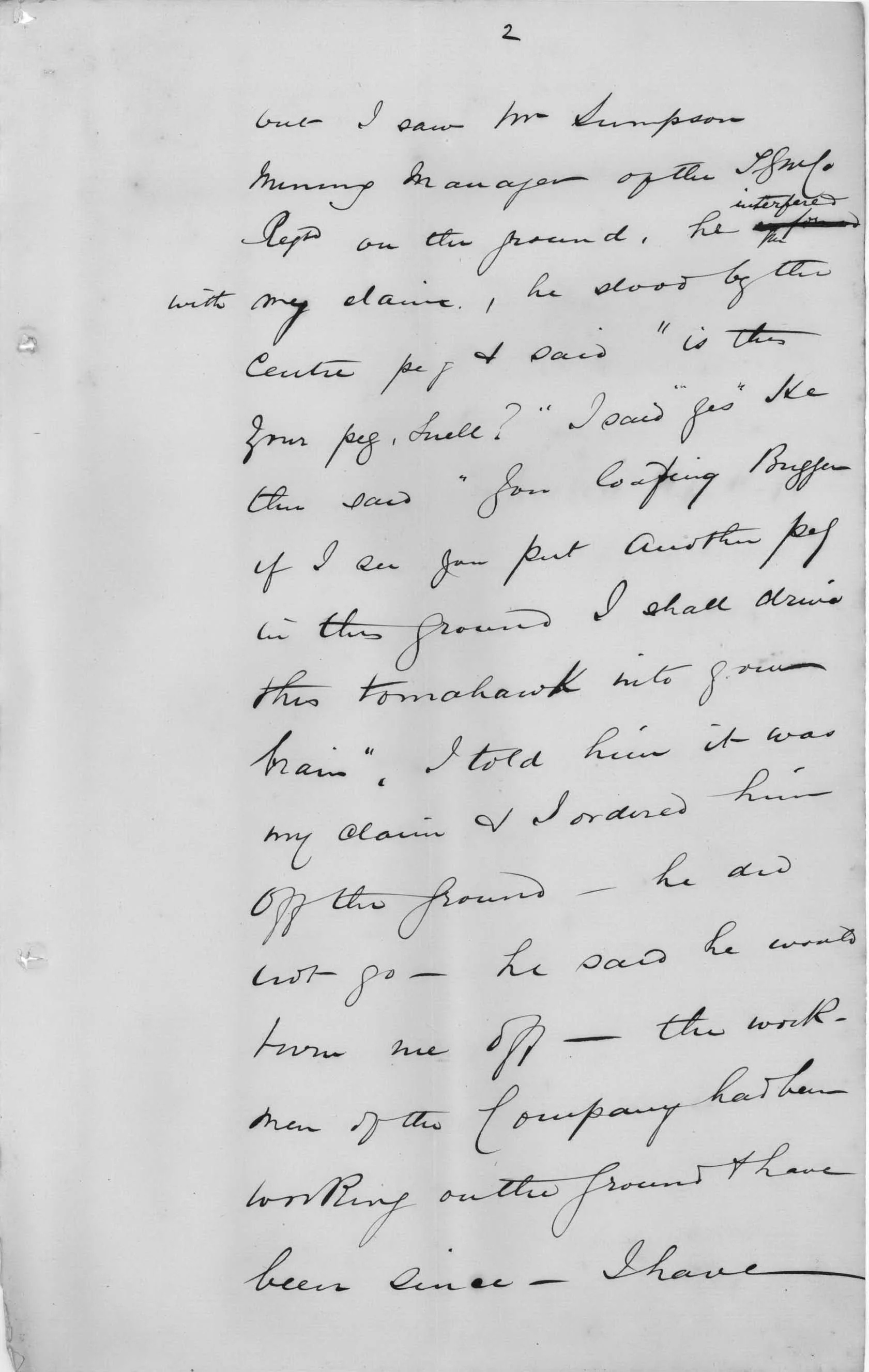

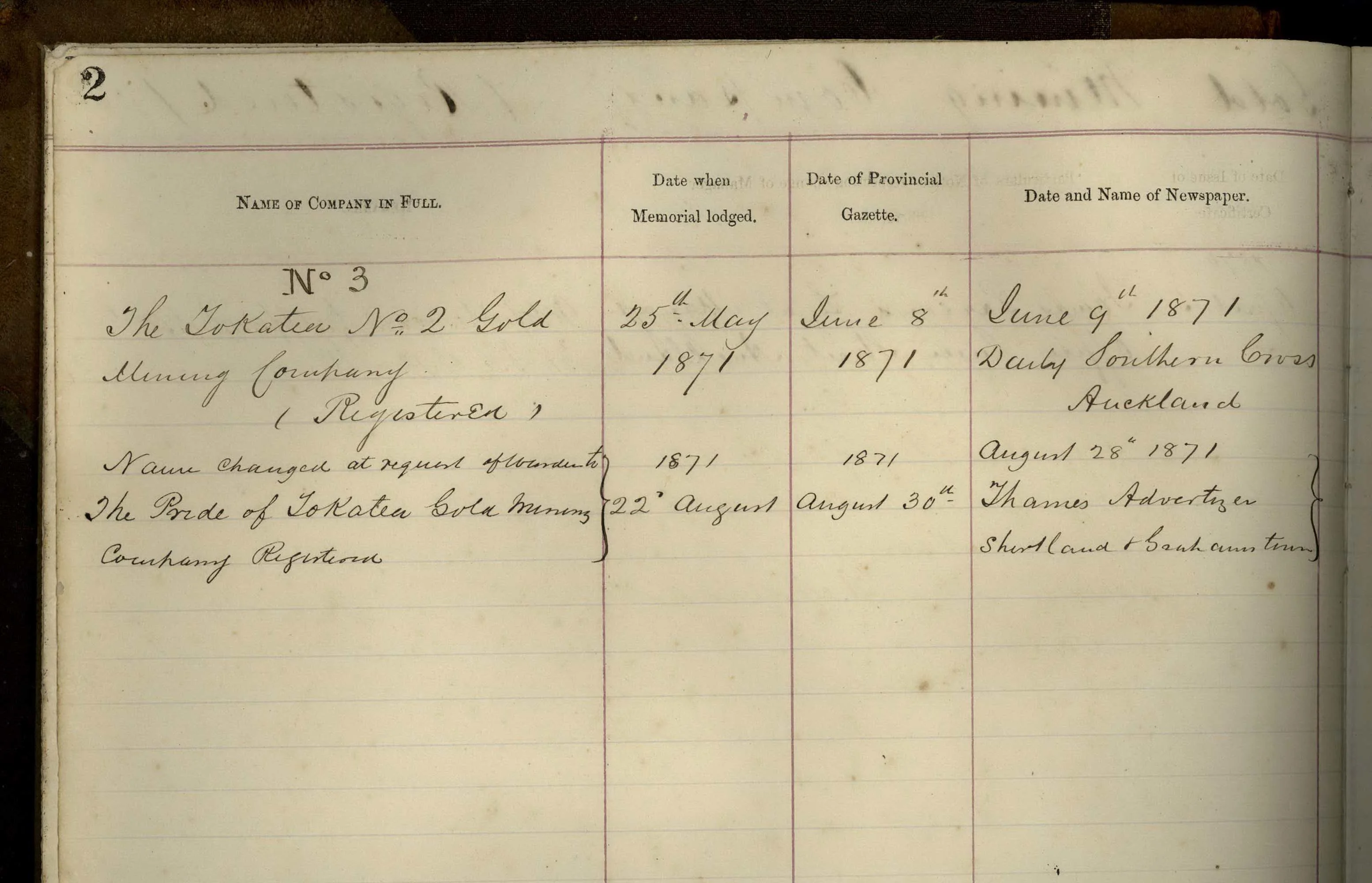

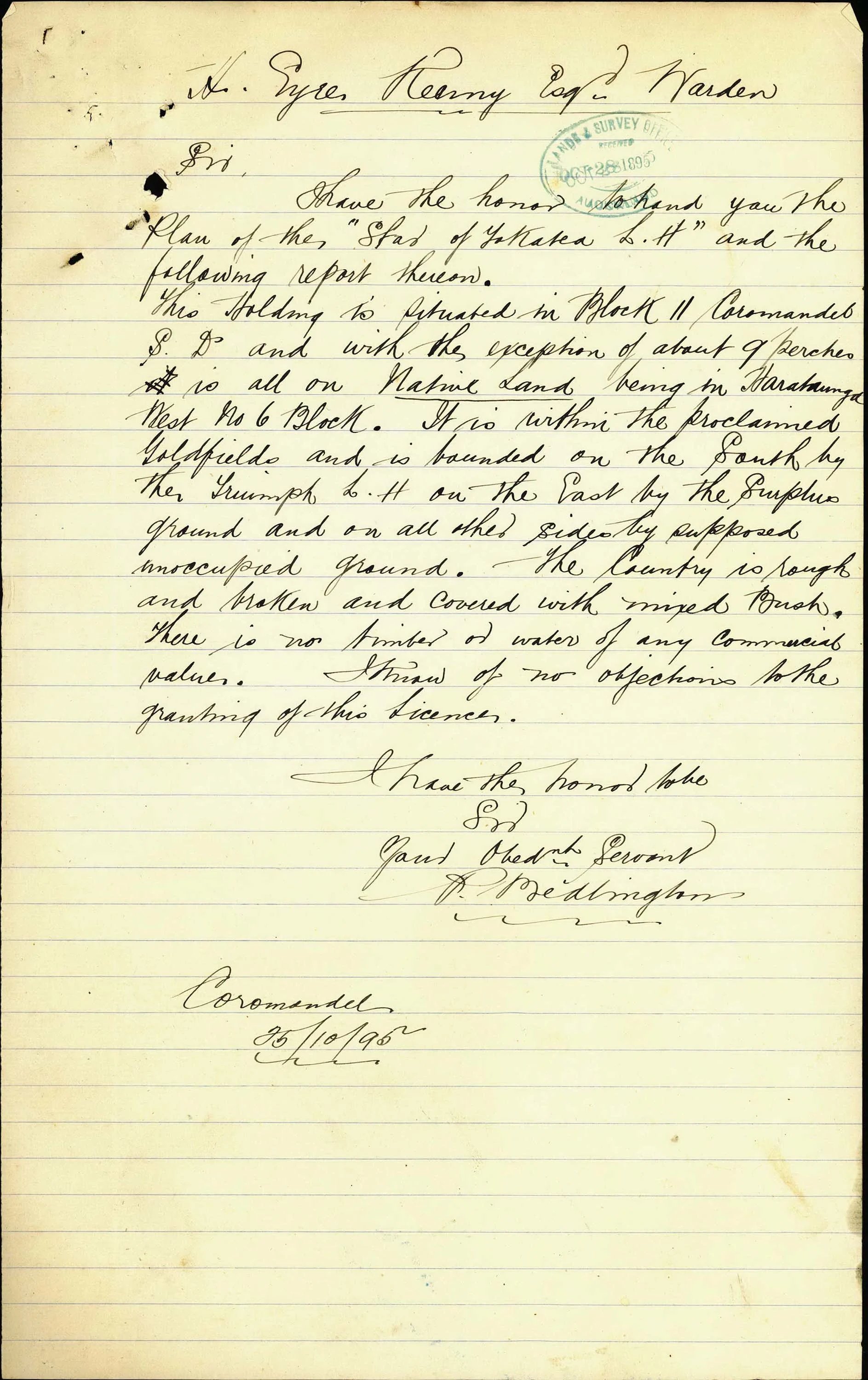

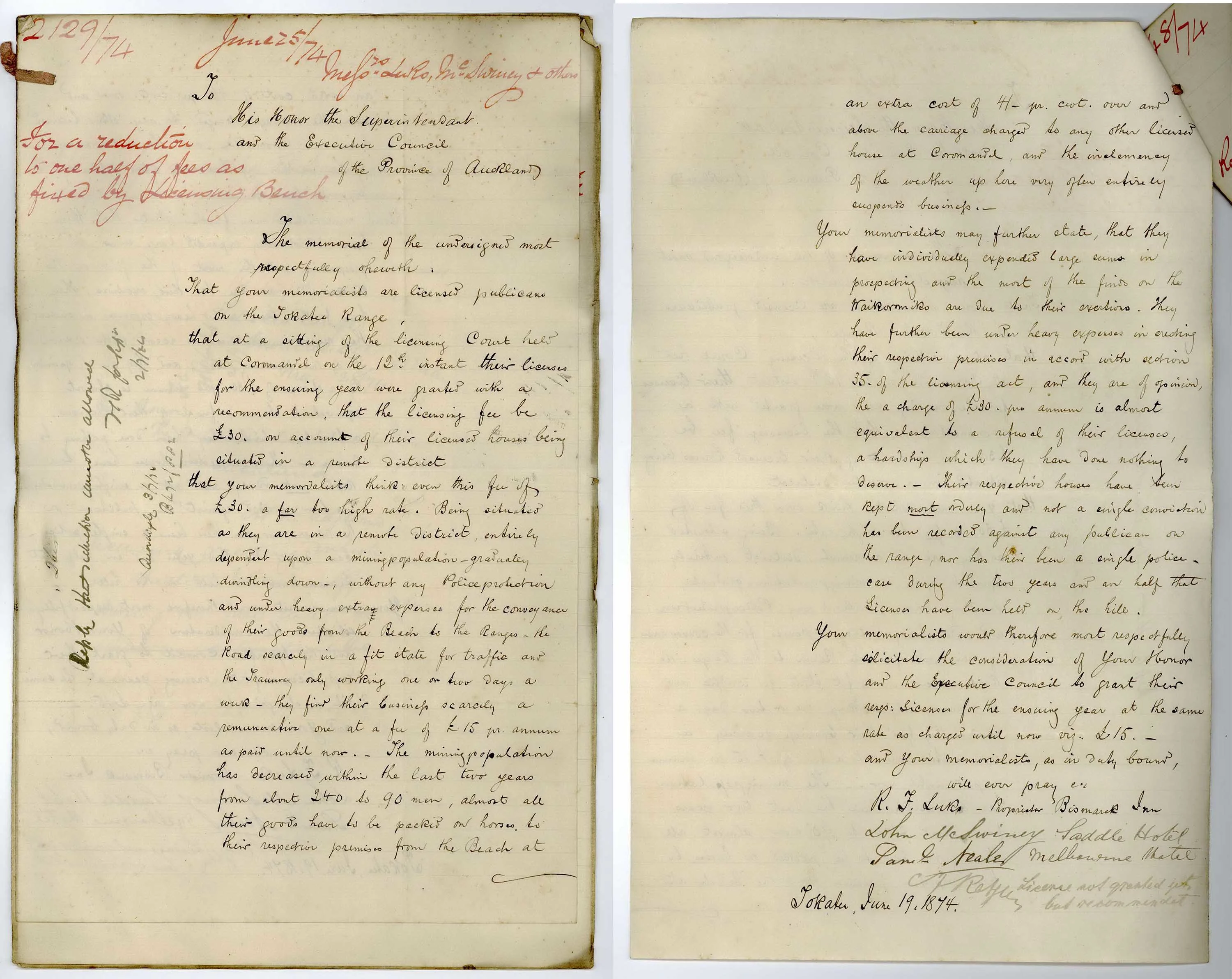

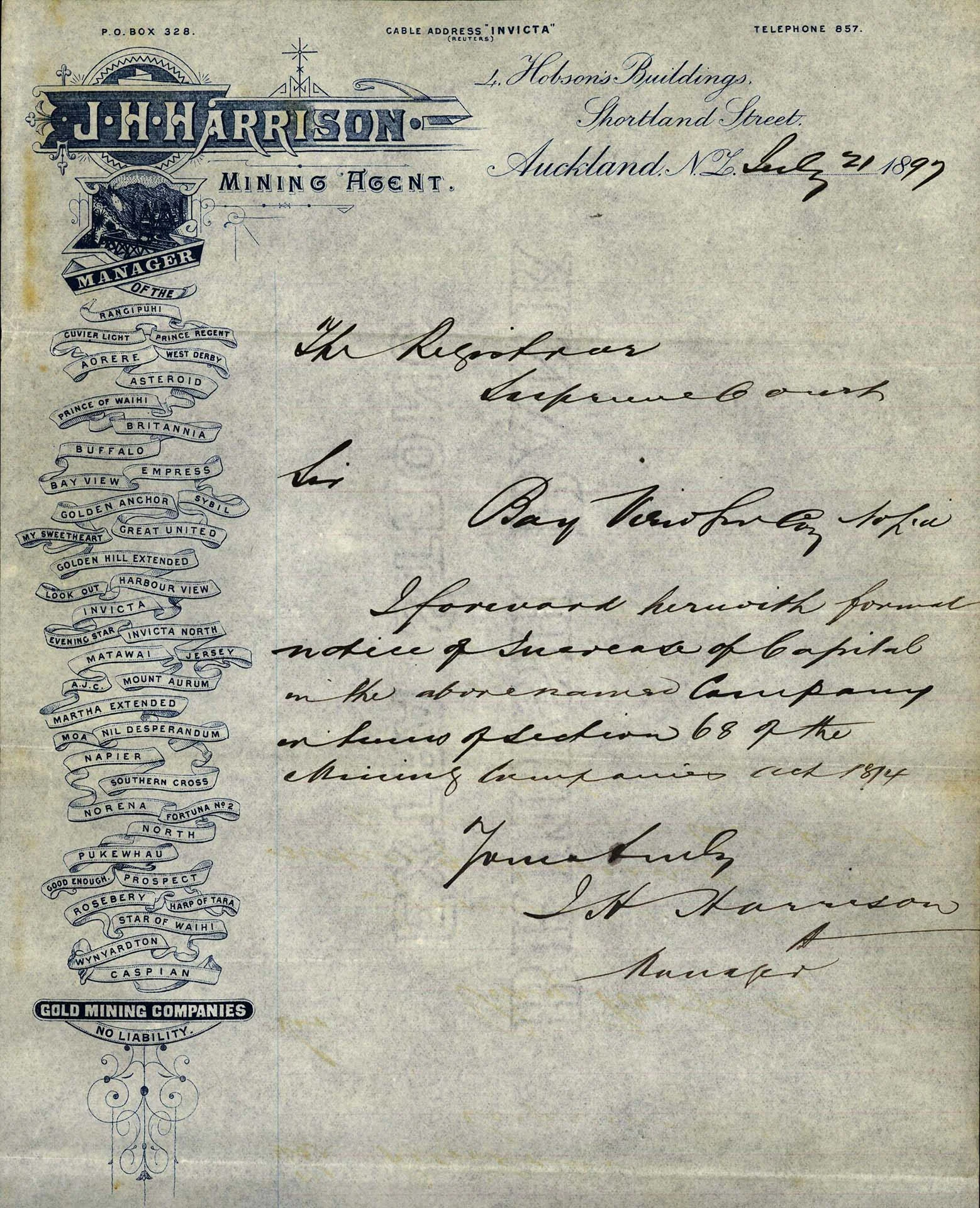

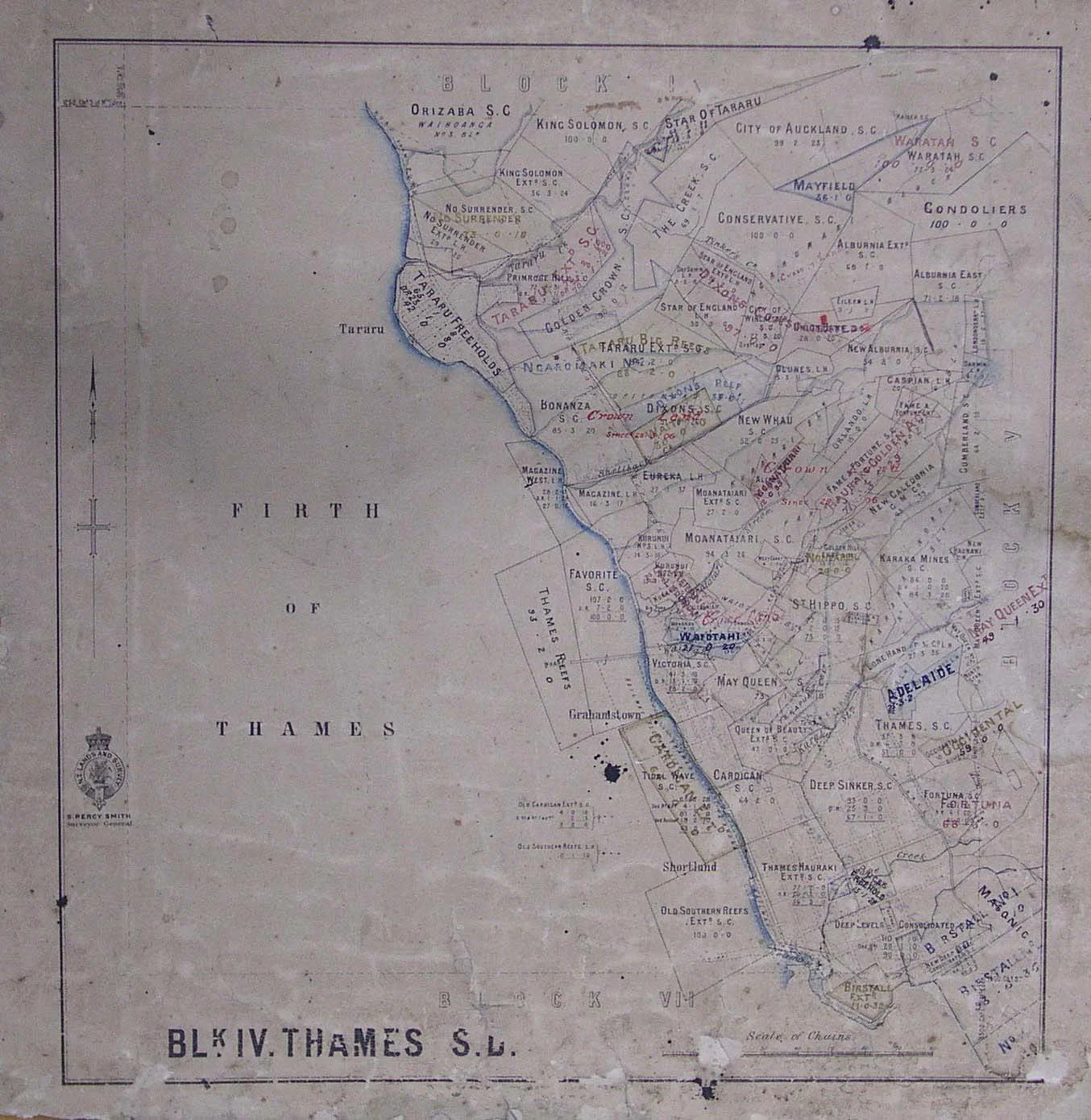

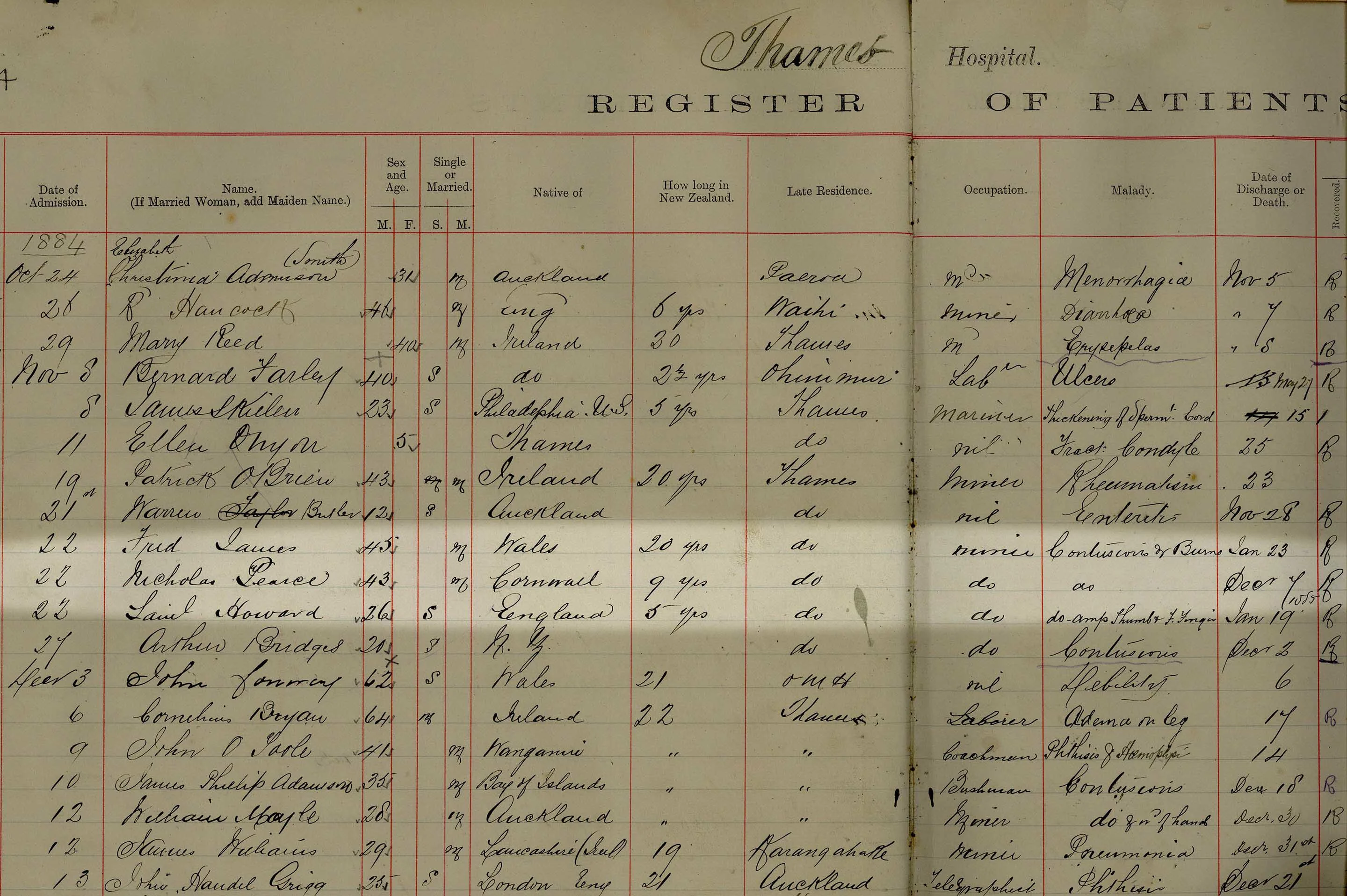

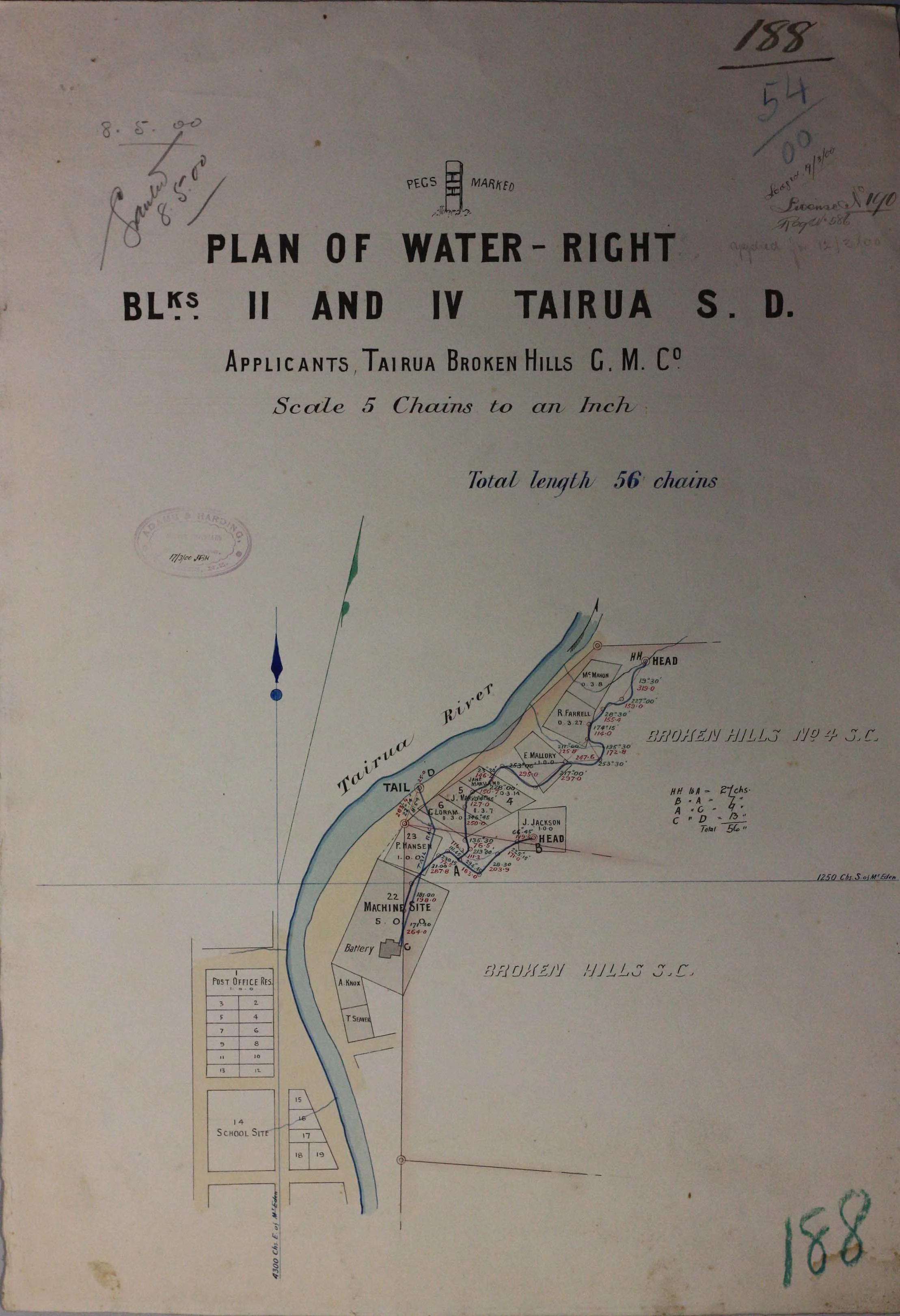

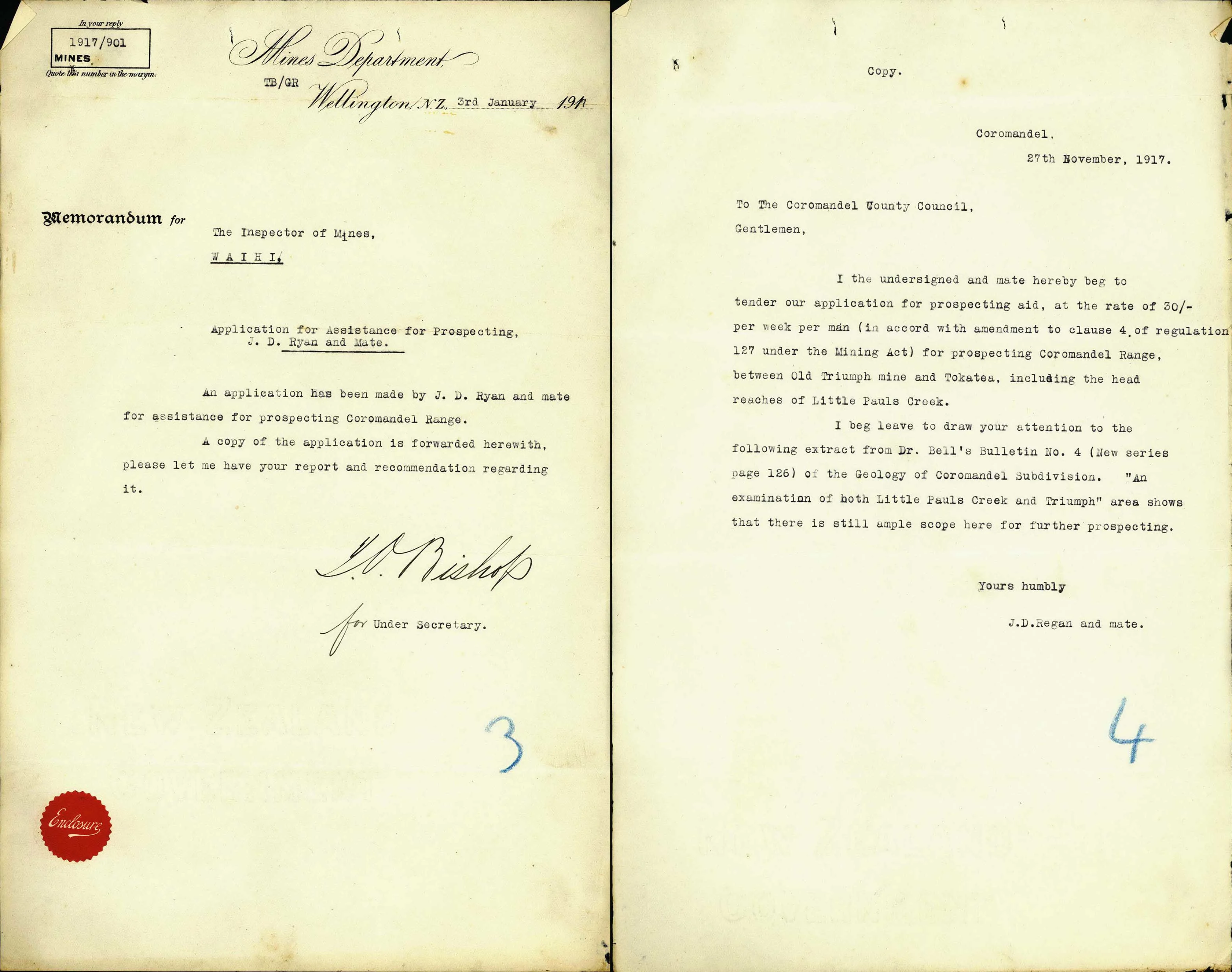

Alluvial gold was first discovered in the Coromandel in the 1850s, and the area was declared a goldfield in 1862 following the discovery of gold-bearing quartz. The Warden's Offices were responsible for the local management of gold mining. Their responsibilities included the resolution of disputes, allocation of residence, business and machine sites, water rights, the administration of agricultural and pastoral (farming) leases, and the hearing of civil and criminal suits within the district.

The Coromandel was declared a goldfield in 1862 after gold was found in the area. Shortly after, in 1867 the Thames goldfield was also proclaimed after negotiations with Maori landowners.

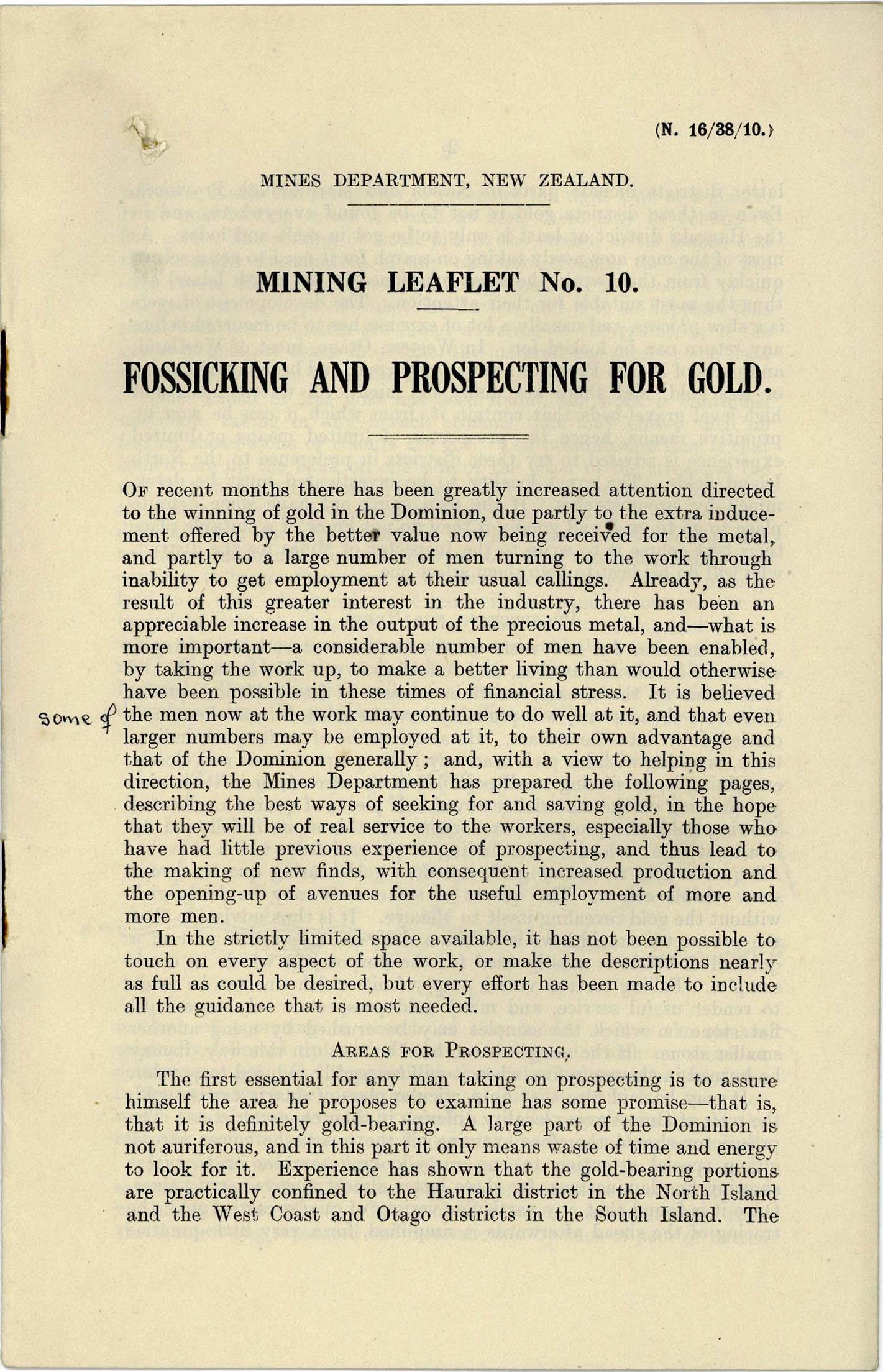

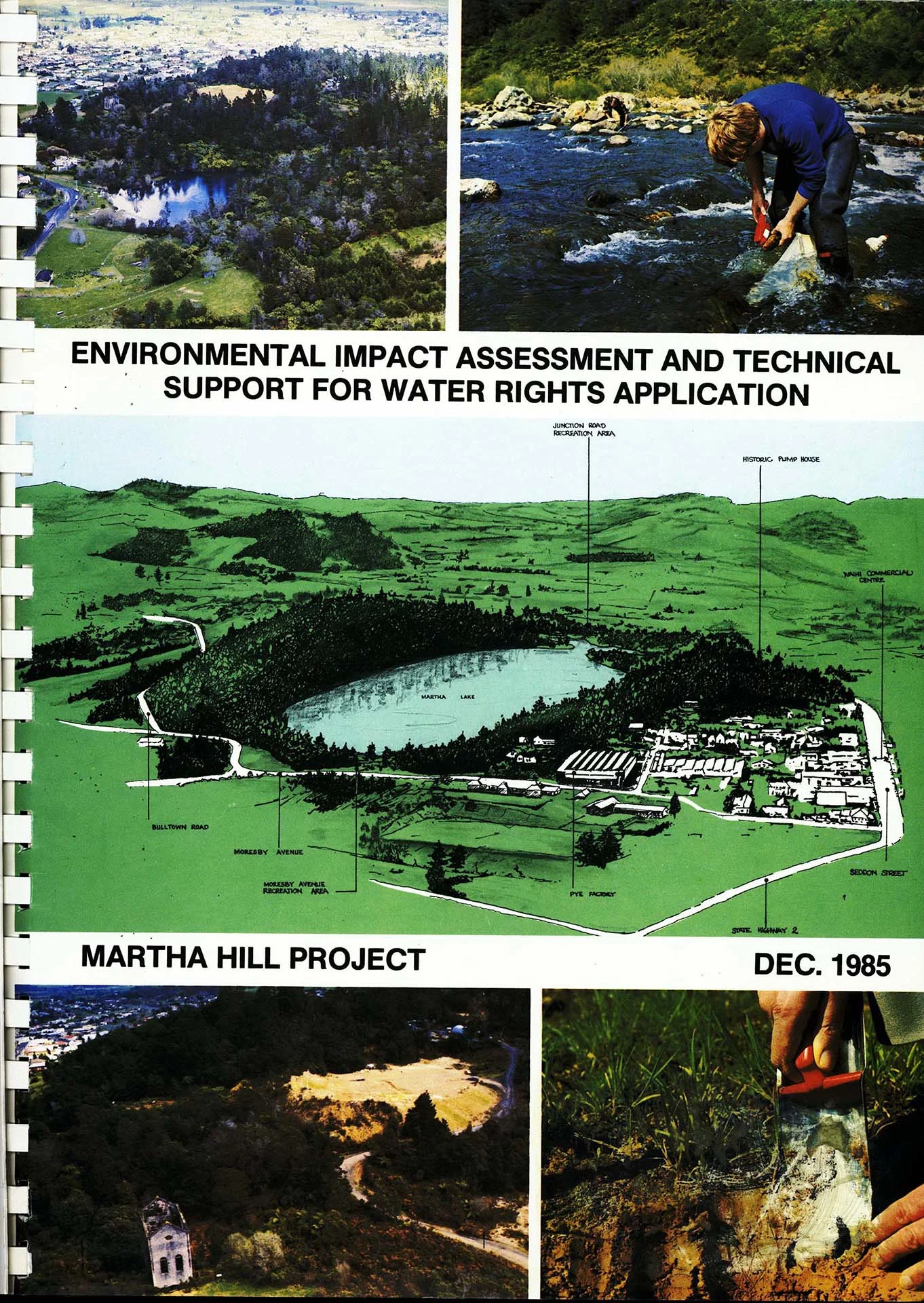

In the early days mining and prospecting rights were issued as long as no-one else had a claim over an area, but a century later, in the 1980s, far more consideration was applied to these applications.

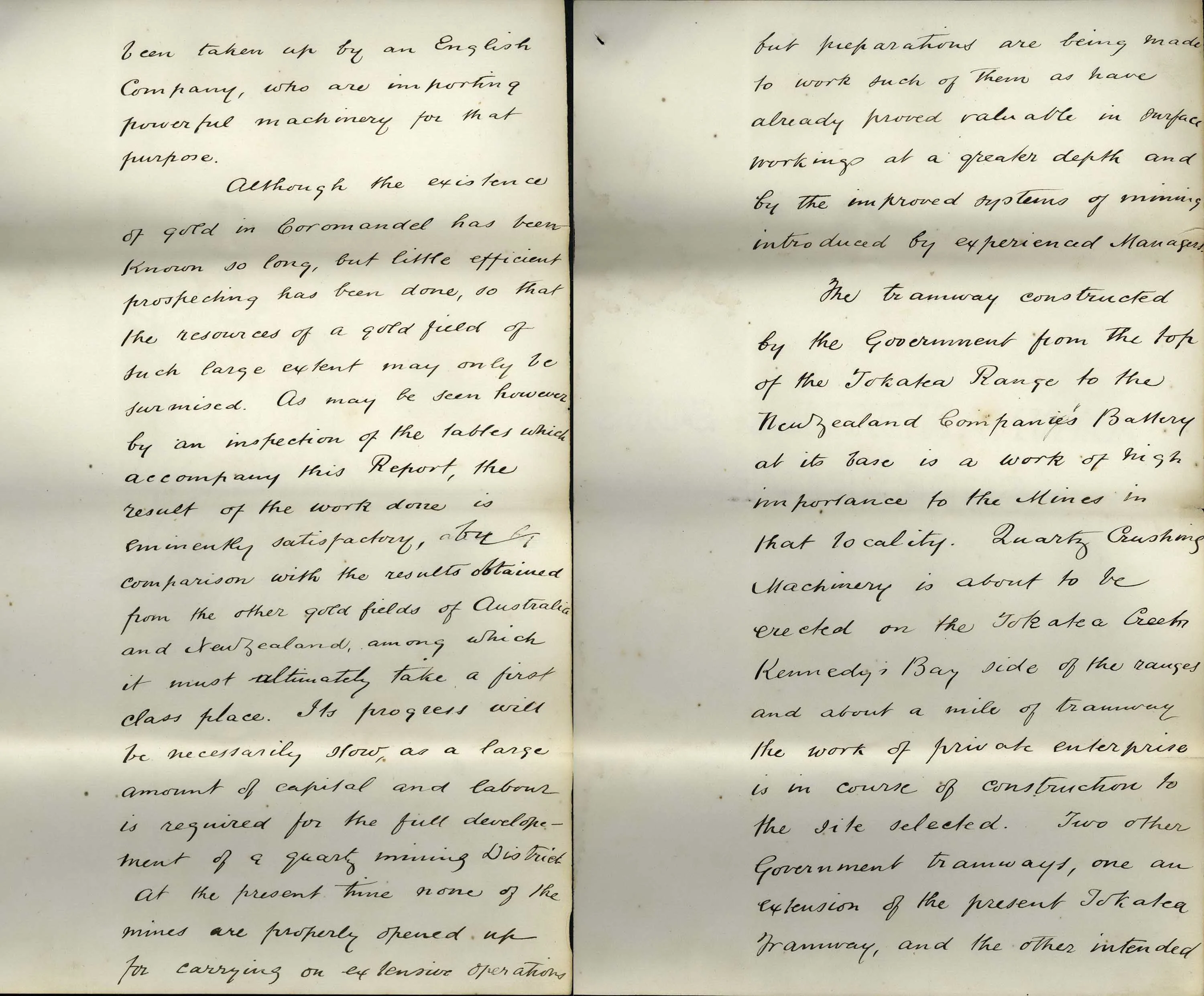

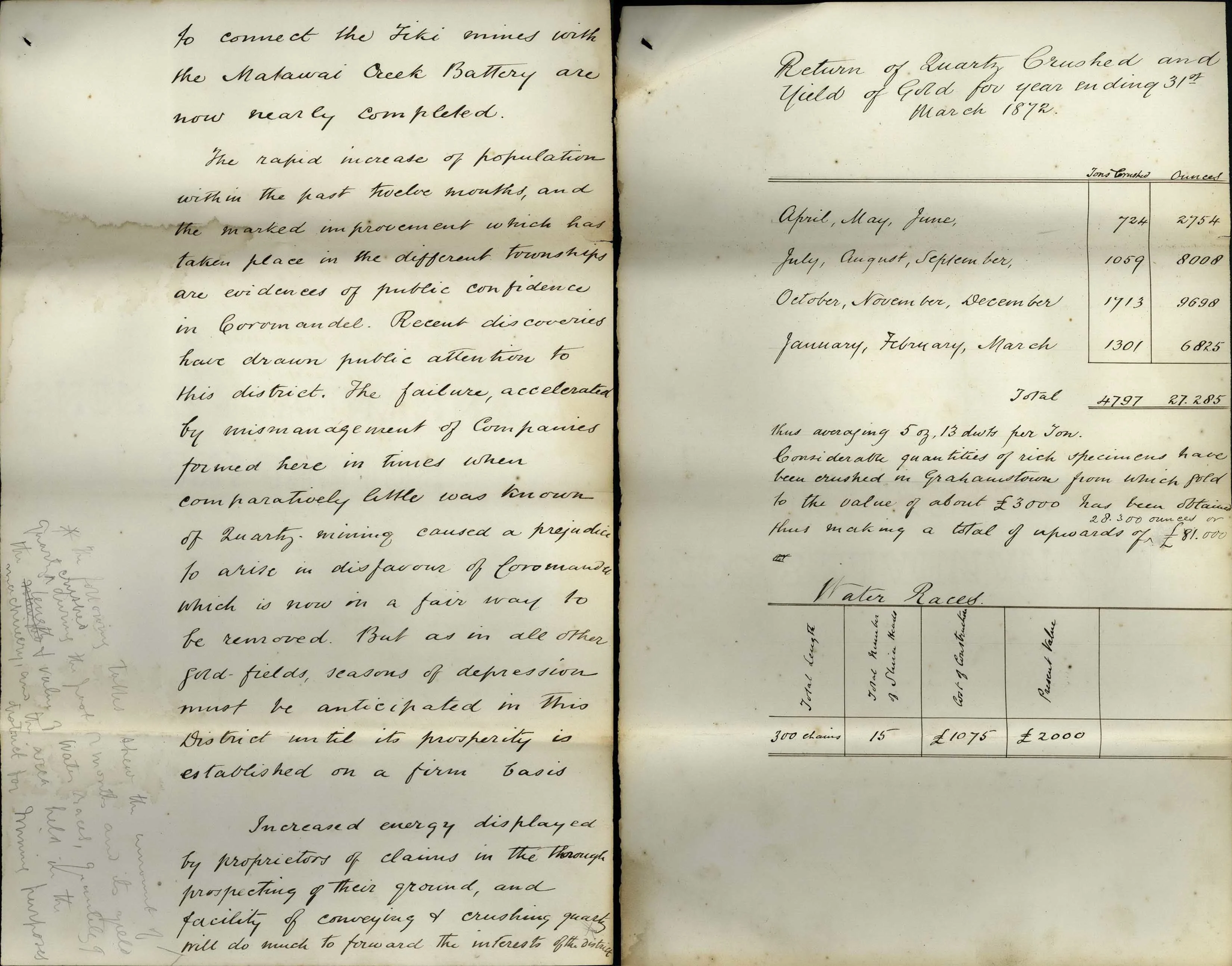

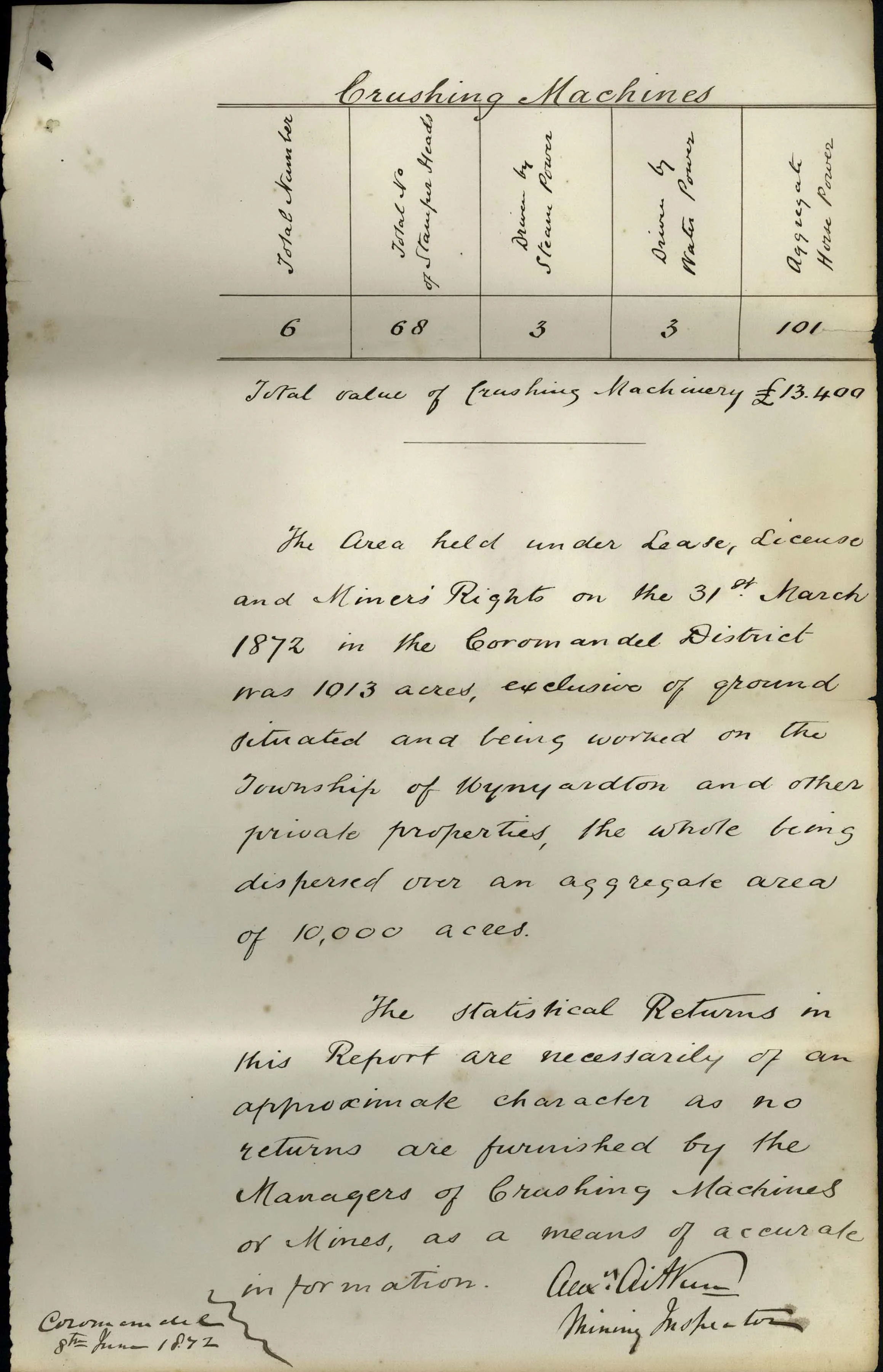

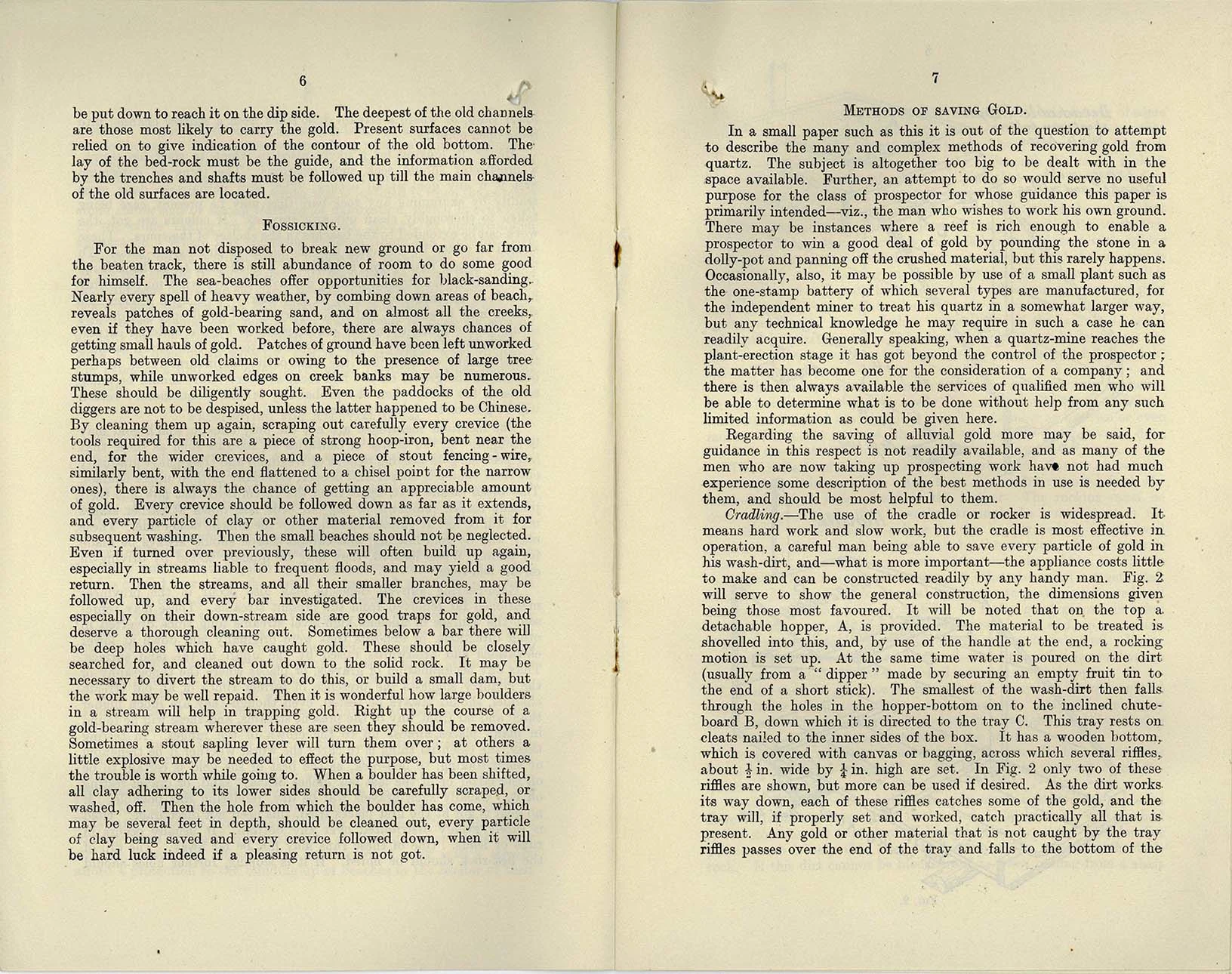

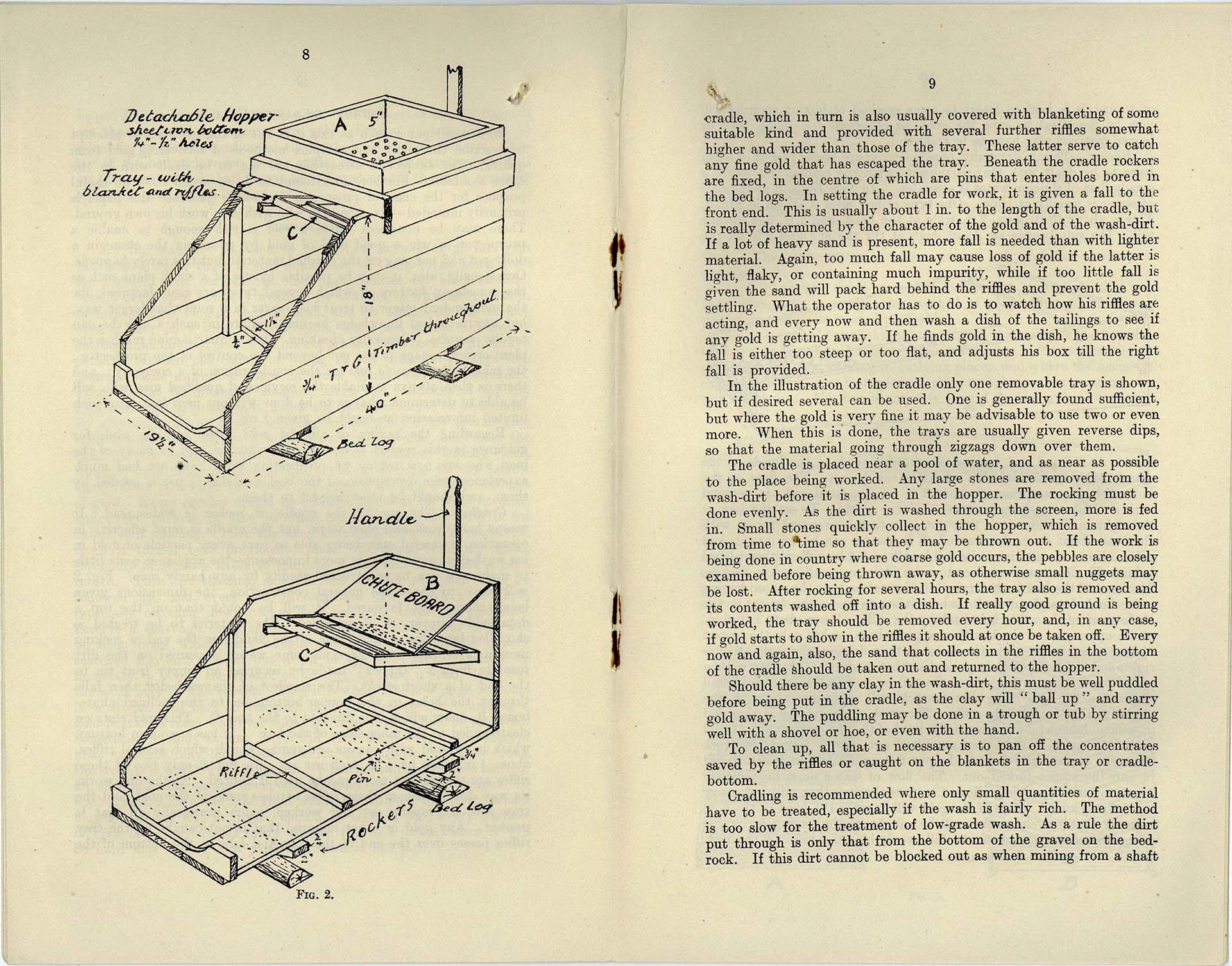

To recover gold from quartz, the rock had to be crushed. Stamper batteries were used to crush the gold-bearing mineral ore and at one time 693 stamper heads within numerous batteries were operating in Thames alone. They were mostly water-powered, and the Thames water race, a man made channel was completed in 1876 to carry water from the Kaueranga River into Thames. These batteries operated almost 24/7, with a break on Sunday mornings to allow for church attendance. Citizens reported that they found the silence unnerving.

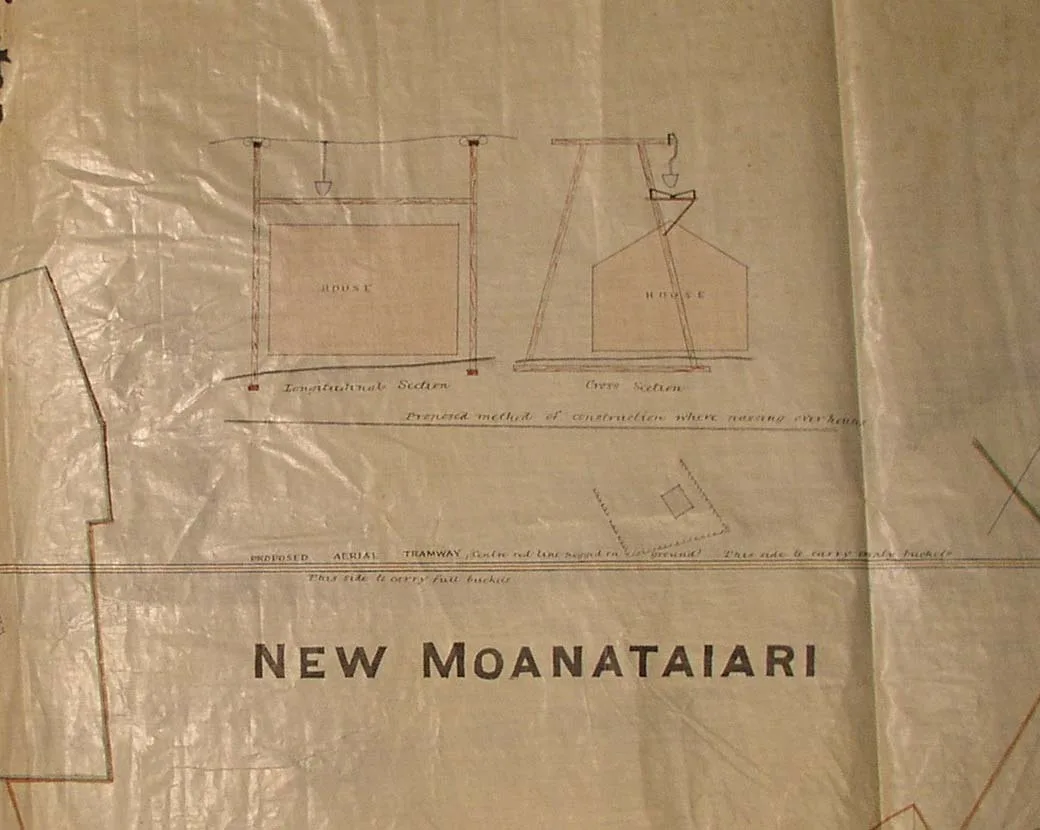

Tramways were used to carry hoppers of mineral ore from mines to the stamper batteries. An 1880 application for an overhead tramway in Thames showed the proposed method of construction when passing over houses. An overhead tramway operated from the Fame and Fortune mine, across the New Moanataiari, the Caledonian and the New Manukau, as well as several houses, to the Fame and Fortune battery.

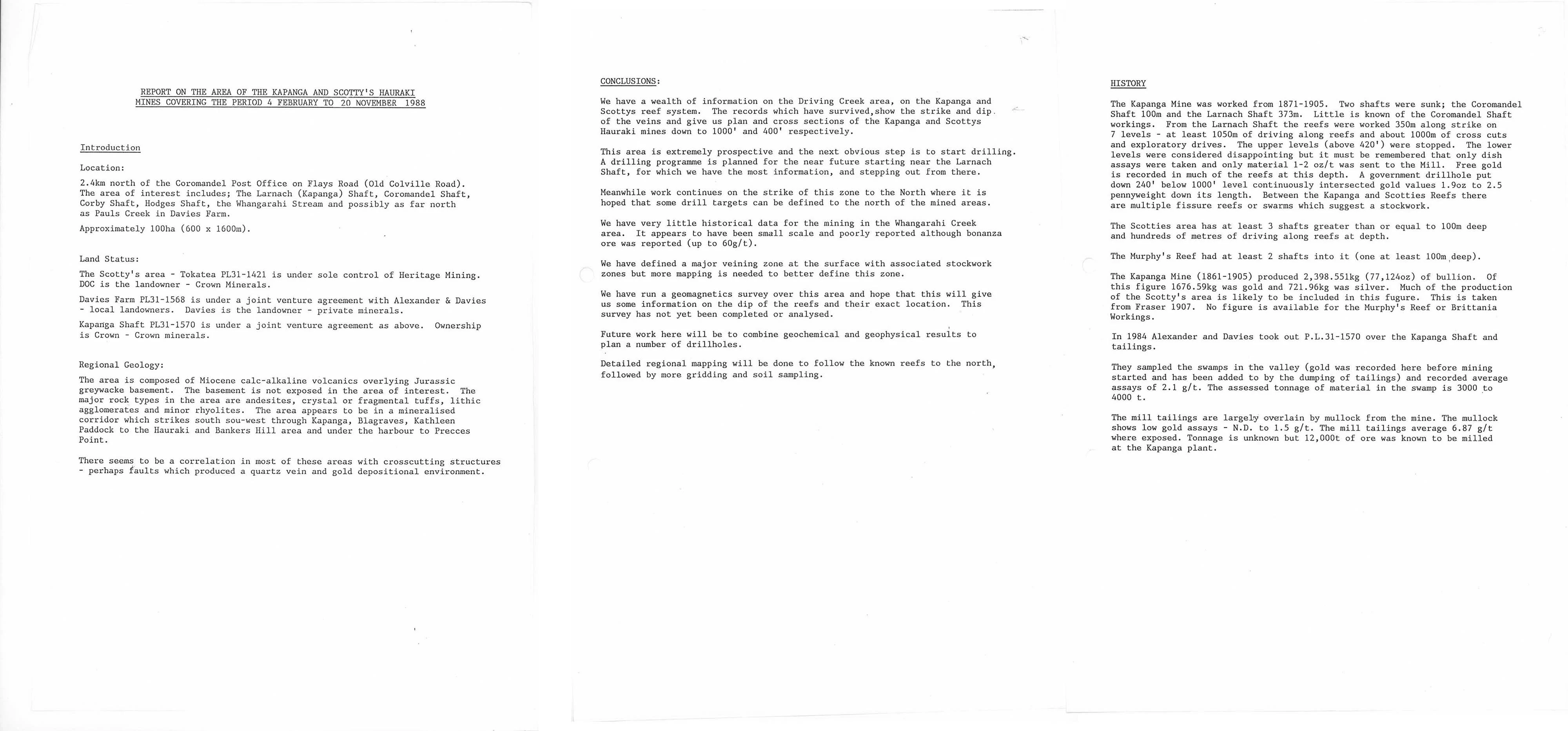

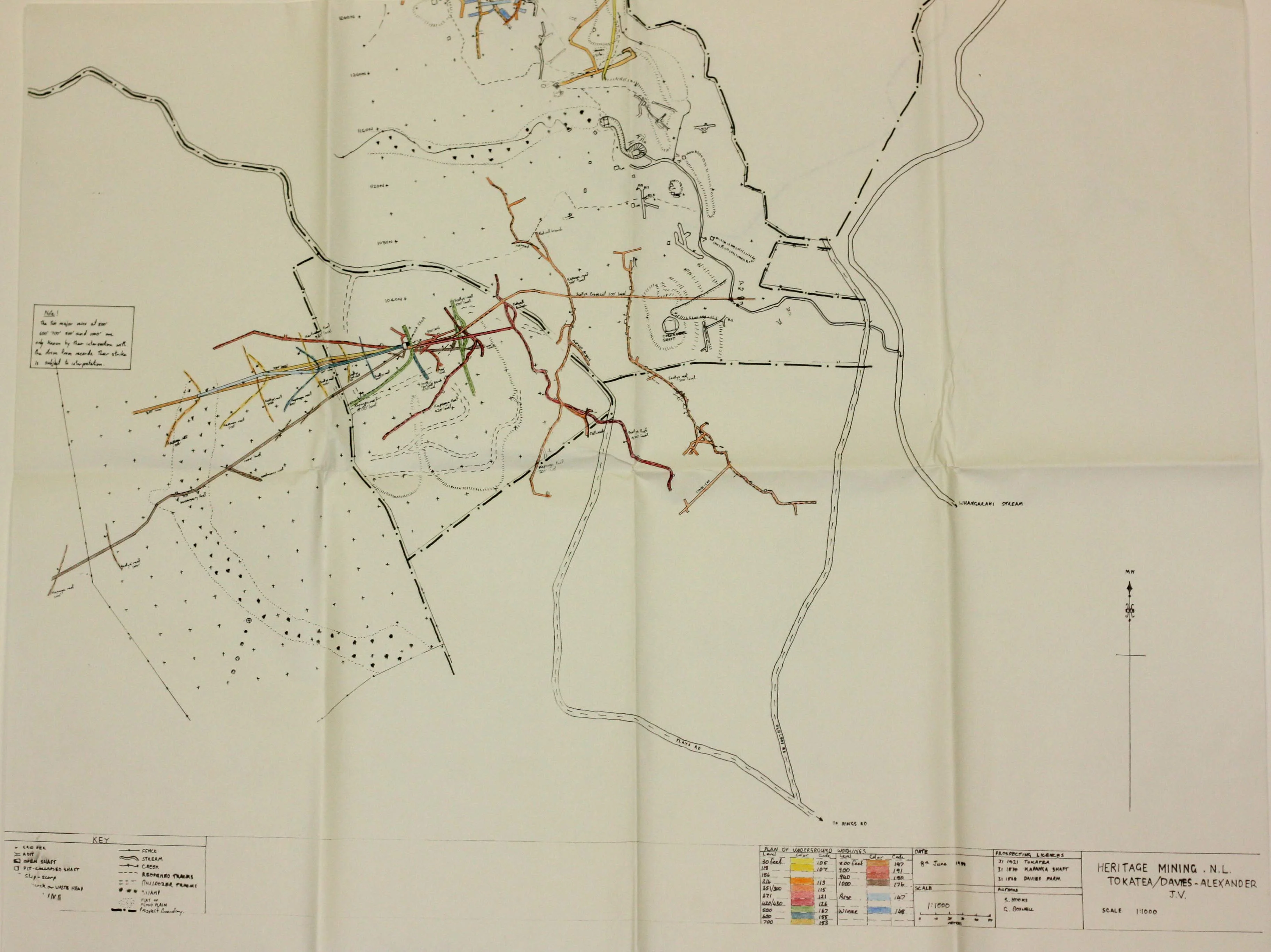

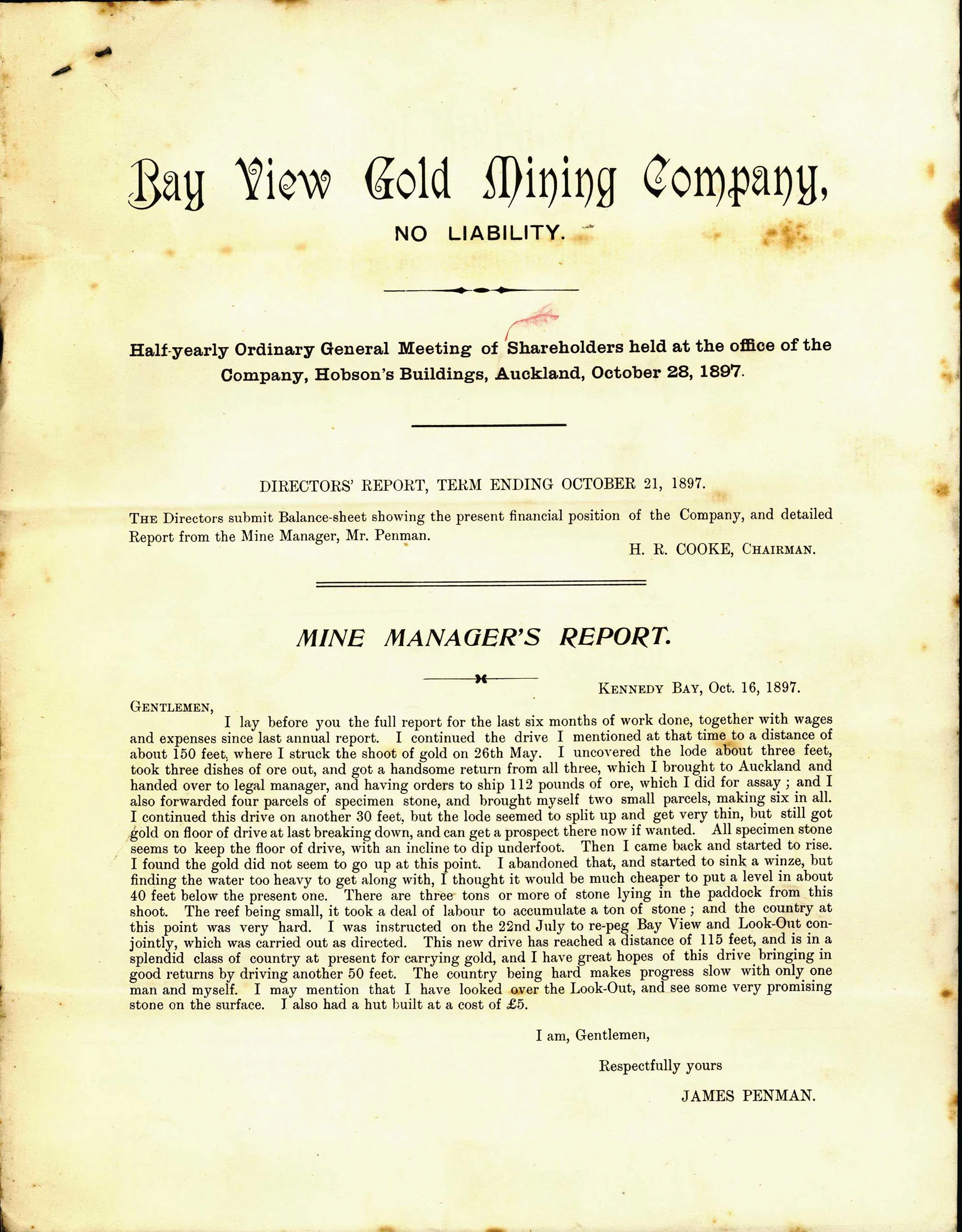

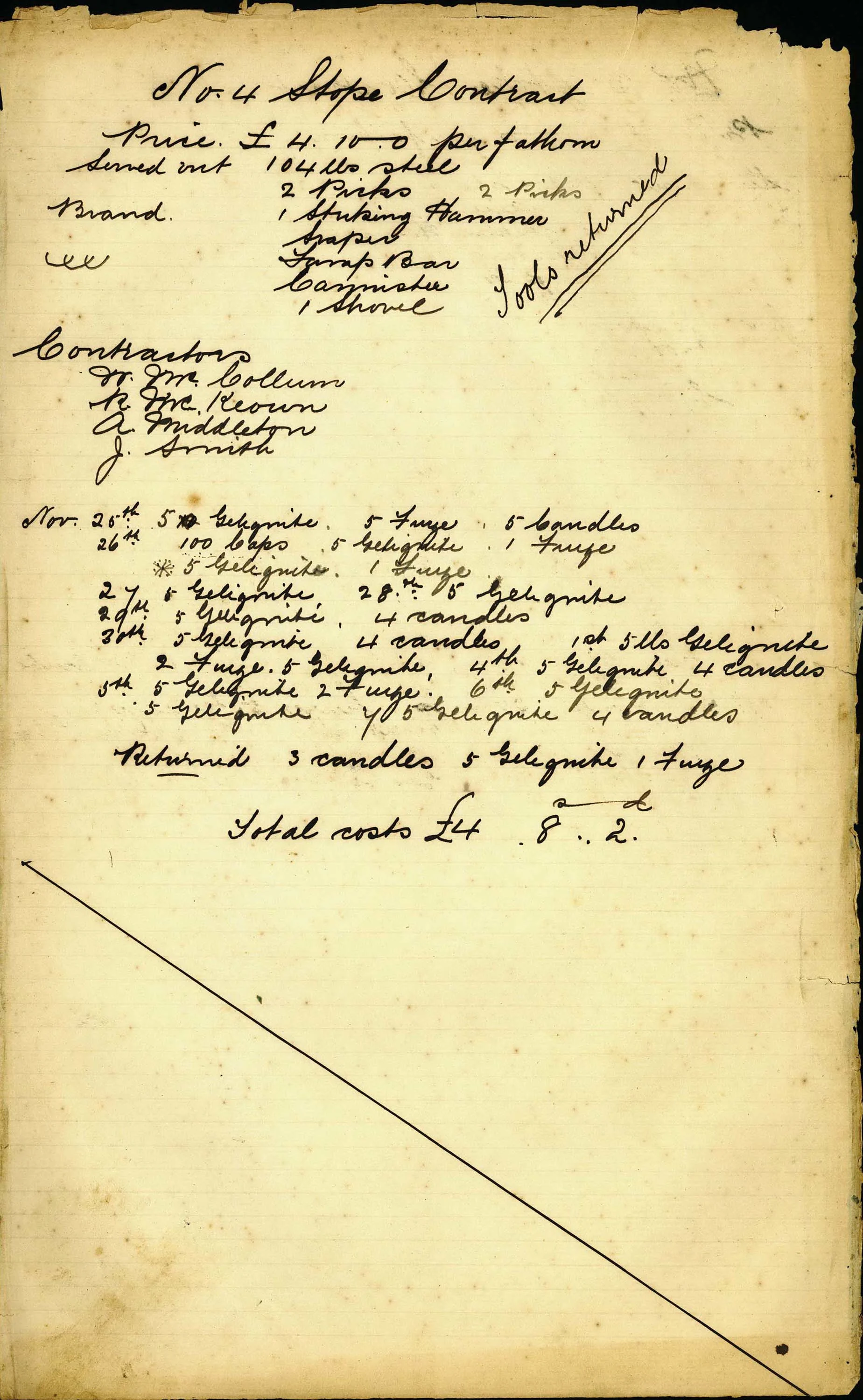

The Kapanga mine was the deepest mine in the Coromandel goldfield, going down to 200 metres below sea-level. From 1862 to 1911 its output was about 30,000 ounces of gold from 17,000 tons of quartz. At the nearby Scotty’s claim, a 140 metre shaft was sunk but returns there never outdid the cost of running the shaft, and it was closed in 1900. It is evident that there was little concern for the environmental impact of goldmining at the time.

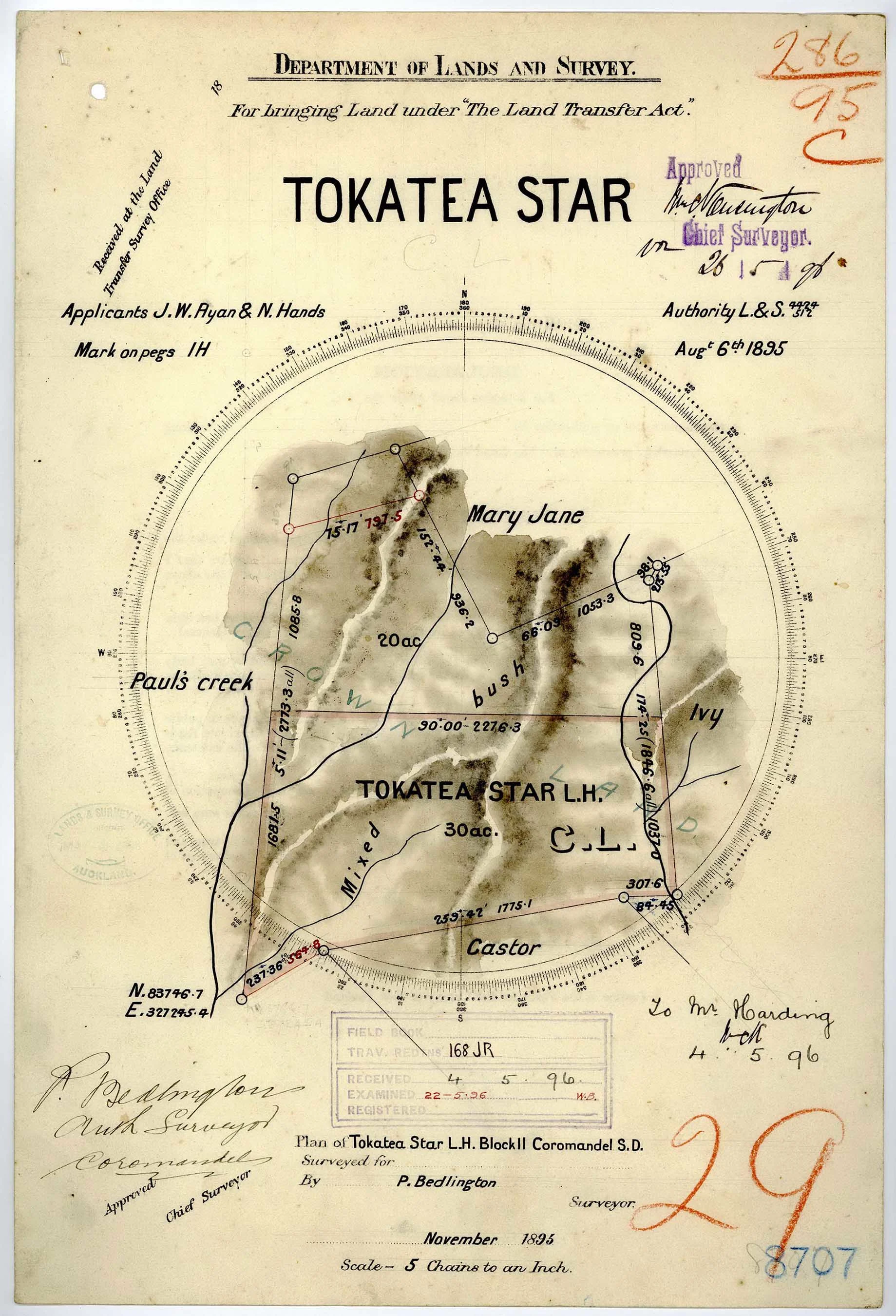

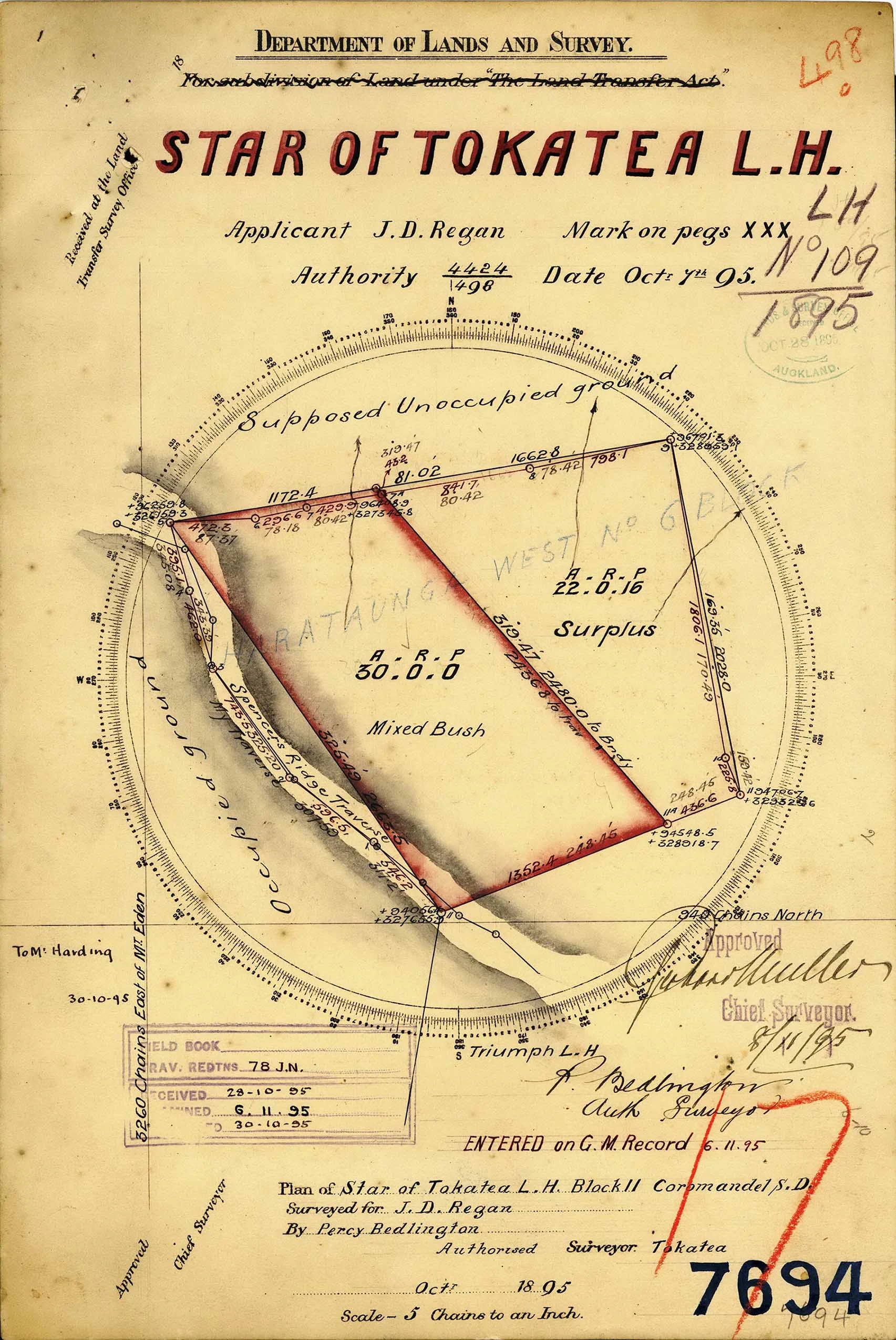

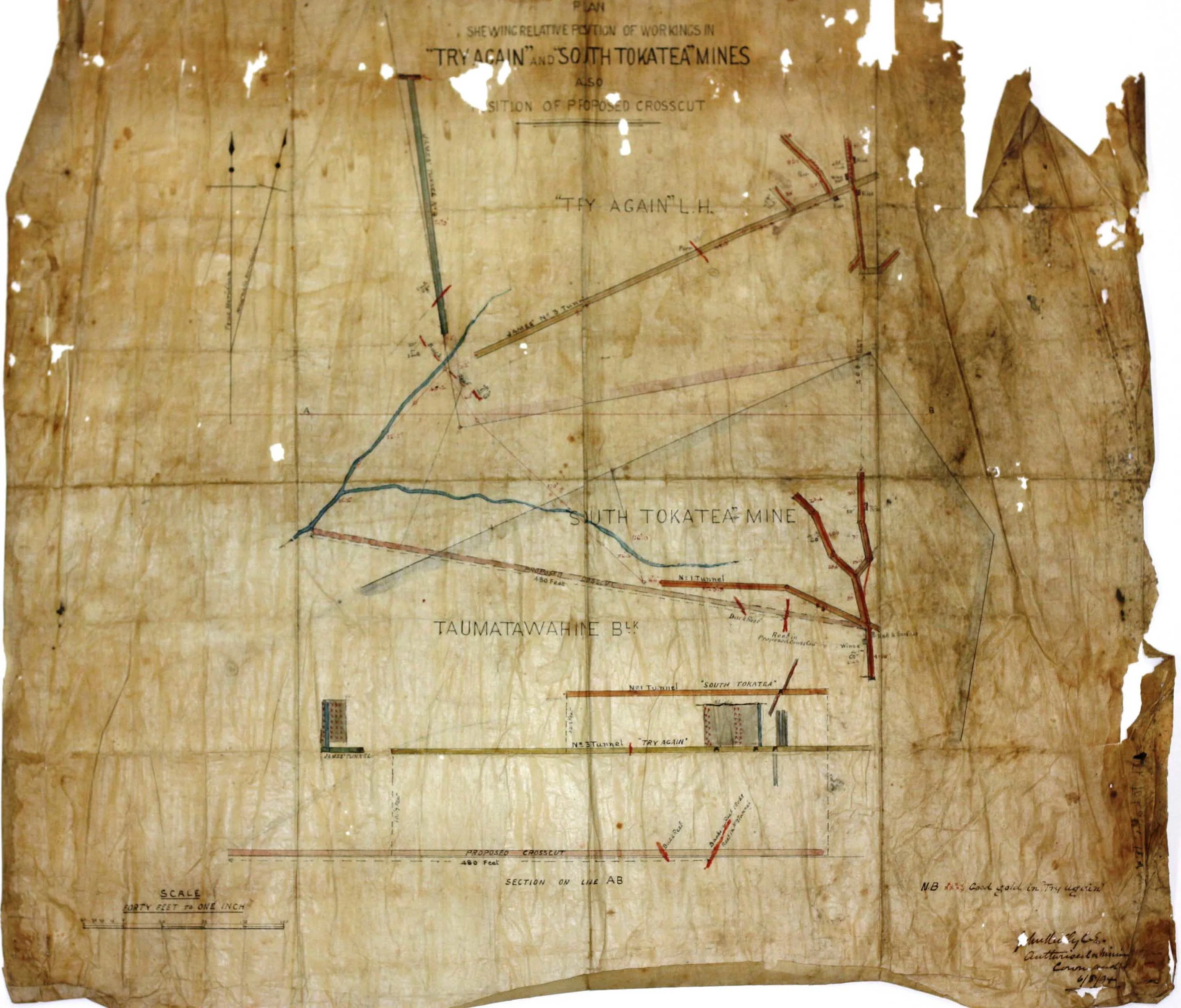

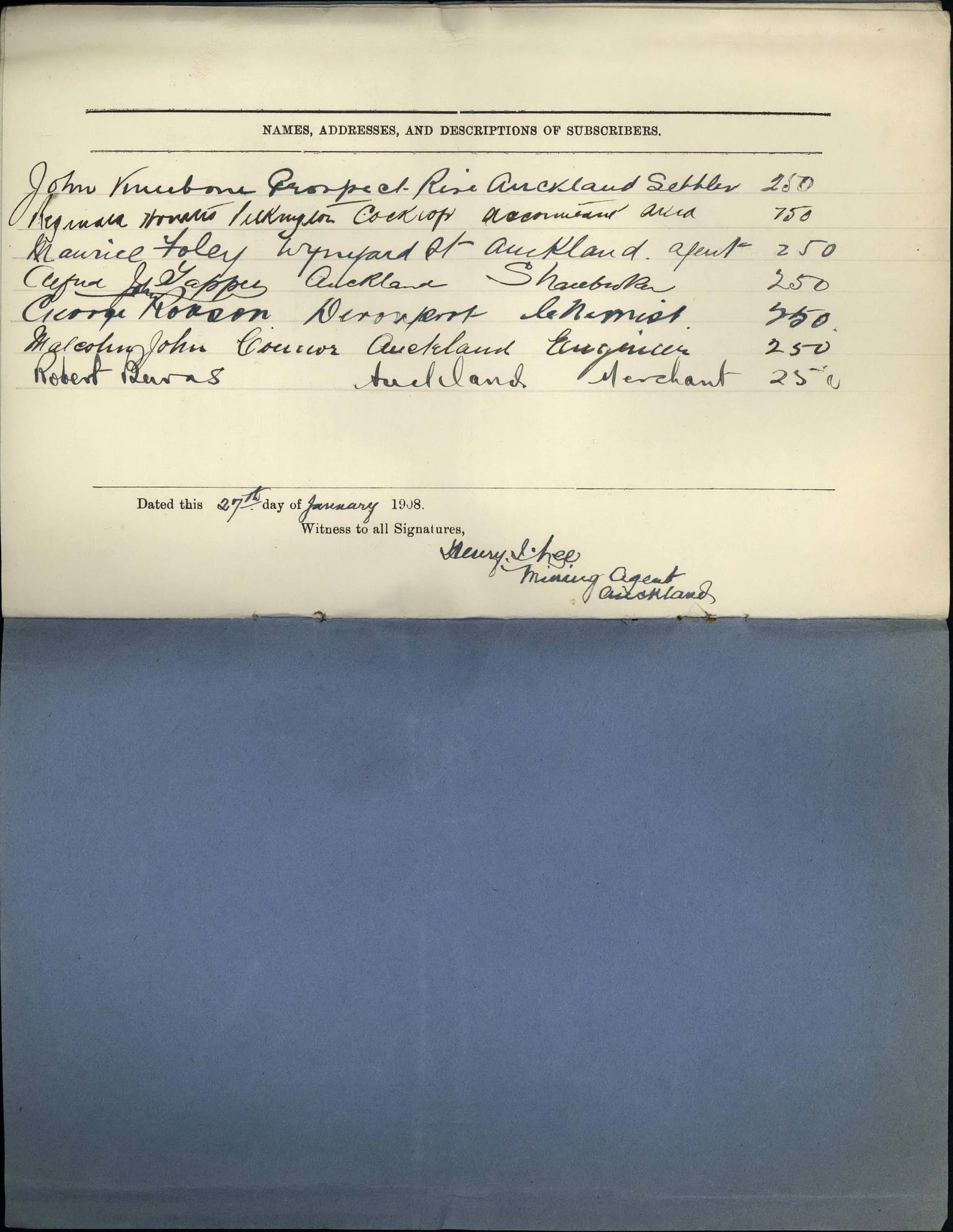

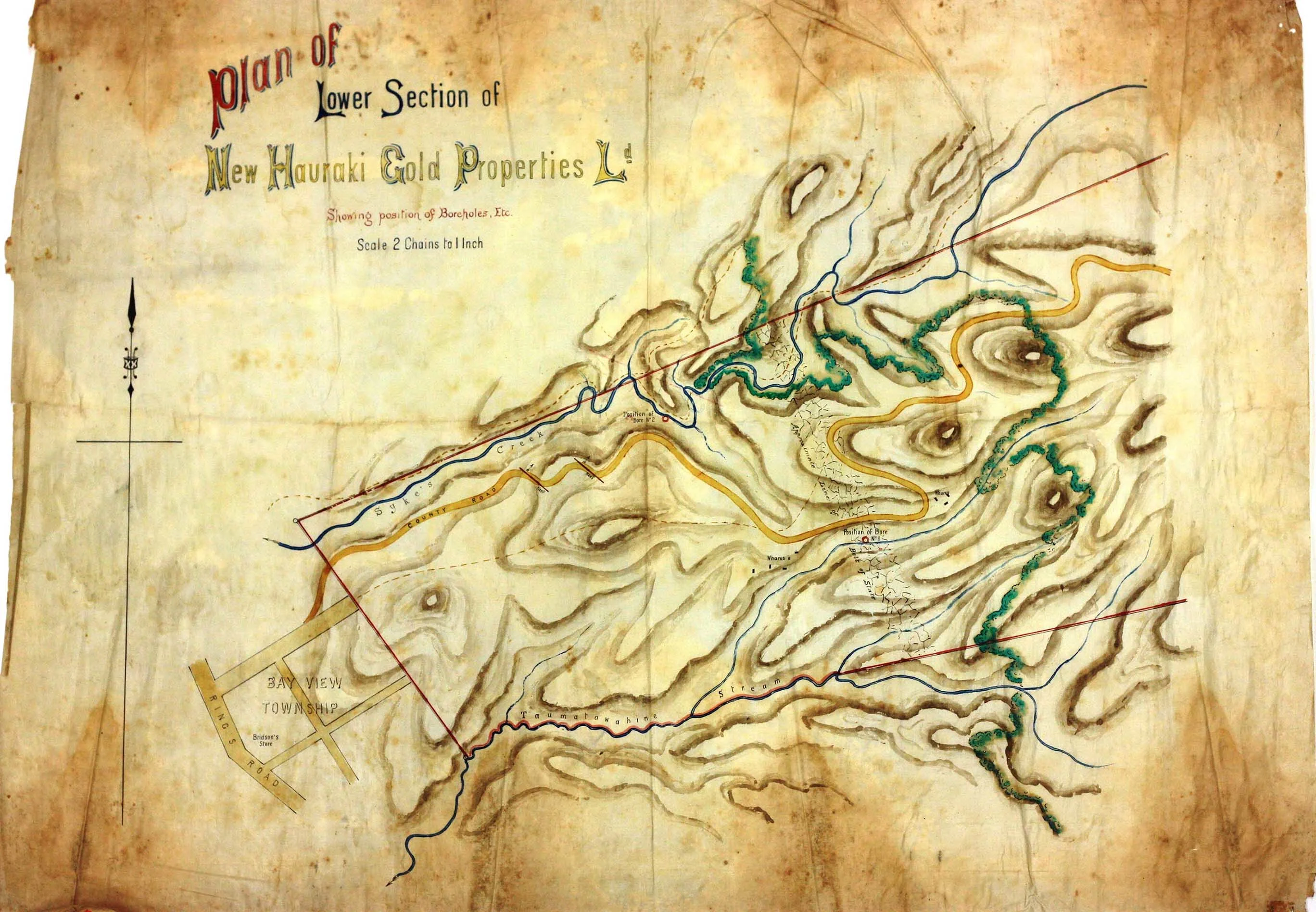

This exhibition looks at the early days of goldmining on the peninsula, then shows a more detailed view of one area, the Tokotea (the ridge above Coromandel town), followed by some aspects of life in the goldfields. Many of the images displayed here have been taken from the records of the Warden’s Courts.