The rise of the Mau and the fall of colonial rule in Sāmoa

The Mau movement for Sāmoan independence in the archives.

Sāmoa filemu pea, ma si o’u toto ne’i ta’uvalea, a ia aoga lo’u ola mo lenei mea.

(My blood has been spilt for Sāmoa. I am proud to give it. Do not dream of avenging it, as it was spilt in peace. If I die, peace must be maintained at any price.)

- Chief Tupua Tamasese Lealofi III; translated by RNZ

Even as he lay dying – shot by New Zealand police at a peaceful protest in Apia – Chief Tupua Tamasese Lealofi III refused to condone violence in the fight for Sāmoan independence.

His last words reveal a man and a movement ahead of their time. A few years post-Parihaka and some decades pre-Gandhi, Tamasese was one of just a few early 20th-century leaders to employ nonviolent resistance against colonial rule.

Sāmoan independence in the archives

Our records tell the story of the end of colonial rule in Sāmoa – and their removal to Aotearoa New Zealand is part of it.

Records created by the British Consul and German Colonial Administrations were handed to New Zealand when, at Britain's request, New Zealand seized control of Sāmoa in 1914.

The transfer of records to New Zealand began in 1920, when historian G. Scholefield shipped the archives of the British Consuls to the Dominion Archives in Wellington. He had found the material in a terrible state, damaged by damp and insects and at risk of removal by “interested collectors.” In 1955, archivist R. P. Gilson discovered more material – early papers of the old Sāmoan Government, consular archives, and archives of the German administration from 1900 to 1914. These were also shipped to Wellington.

A closer look at the contents of these records reveals crucial moments and characters in the Mau's fight for independence.

Mamoe and the Mau a Pule – sowing seeds of discontent

The first murmurings of the Mau, Sāmoa’s independence movement, started long before Tamasese took the lead in 1928.

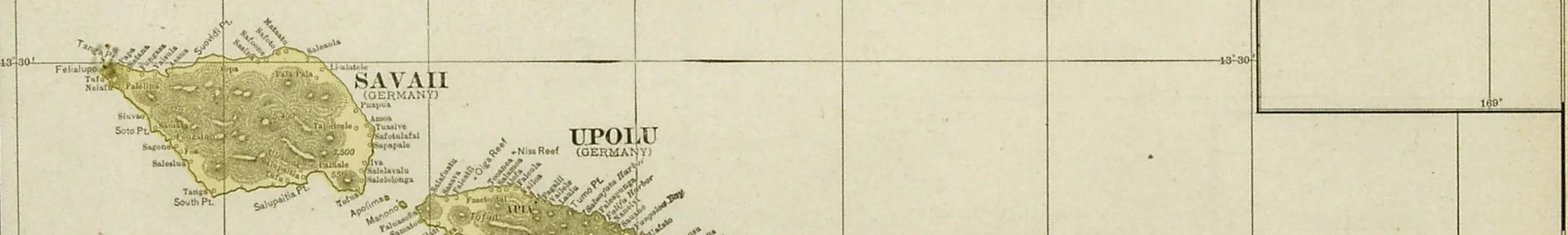

The colonial carve-up of the Tripartite Convention of 1899 drew a crude line through the Sāmoan archipelago, leaving the western islands under German rule. Although its status as a ‘protectorate’ meant German Sāmoa could retain its traditional customs, many didn’t fit in with Berlin’s plans to create a “docile, industrious labour force for German commercial enterprise”.

After hoisting the German Empire’s flag in Apia in 1900, Governor Wilhelm Solf went about abolishing the office of Tupu Sili or king, stating it was the “most radical means of securing peace and quiet in the country”. His words are recorded in a fascinating record in our holdings – "A Documentary Record and History of the Lauati Rebellion 1909” (O Le Mau Lauati).

This assault on Sāmoa’s traditional authority structures came at the same time as a major volcanic eruption and a whooping cough outbreak on the island of Savai’i. Together, in 1908, these circumstances led to unrest among the Maloa o Sāmoa (Sāmoan council of chiefs).

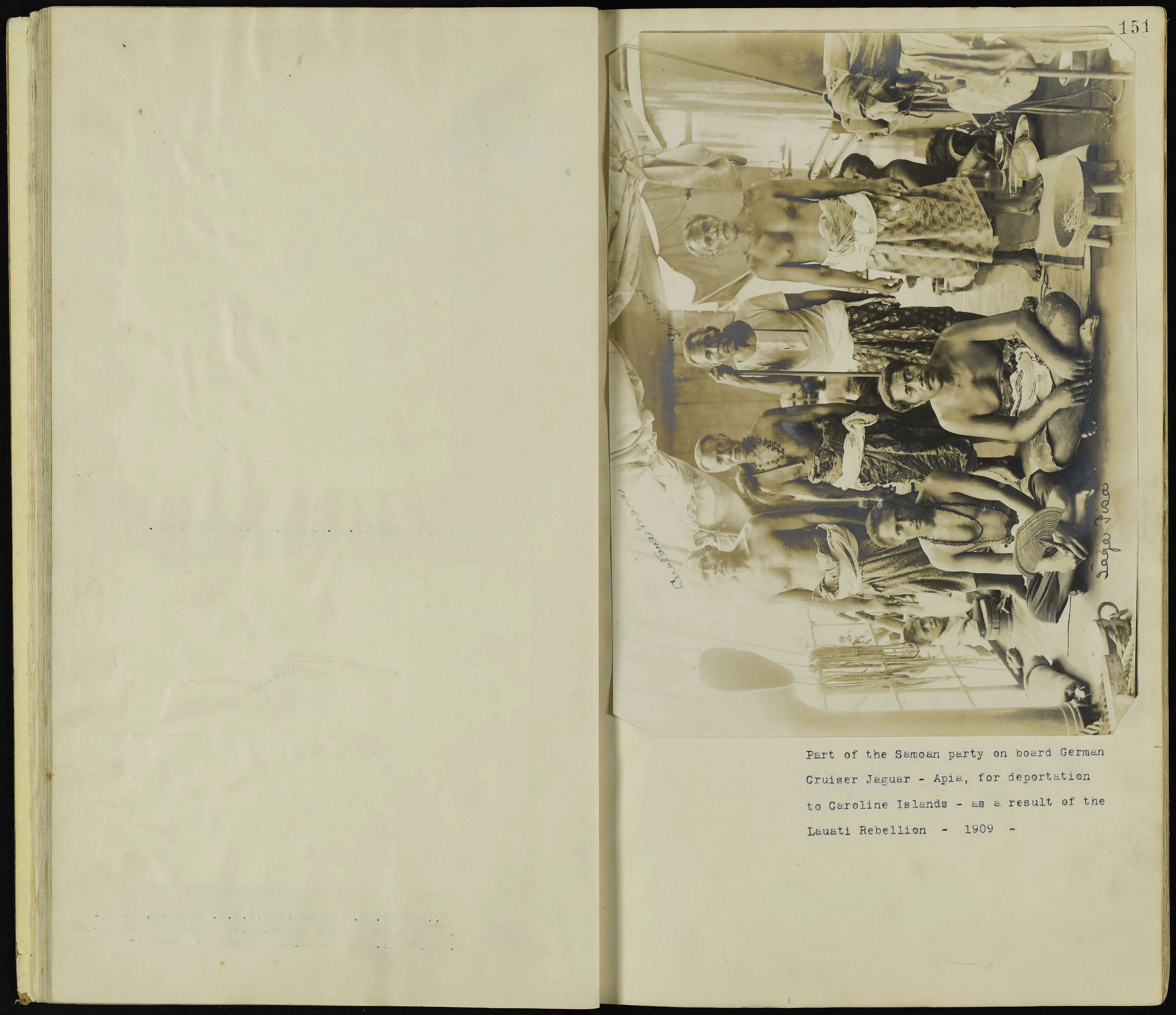

Orator and chief Lauaki Namulau'ulu Mamoe formed a resistance movement opposing the German colonial administration called the Mau a Pule – mau meaning ‘opinion’, and pule the collective name given to several influential orator groups on Savai`i.

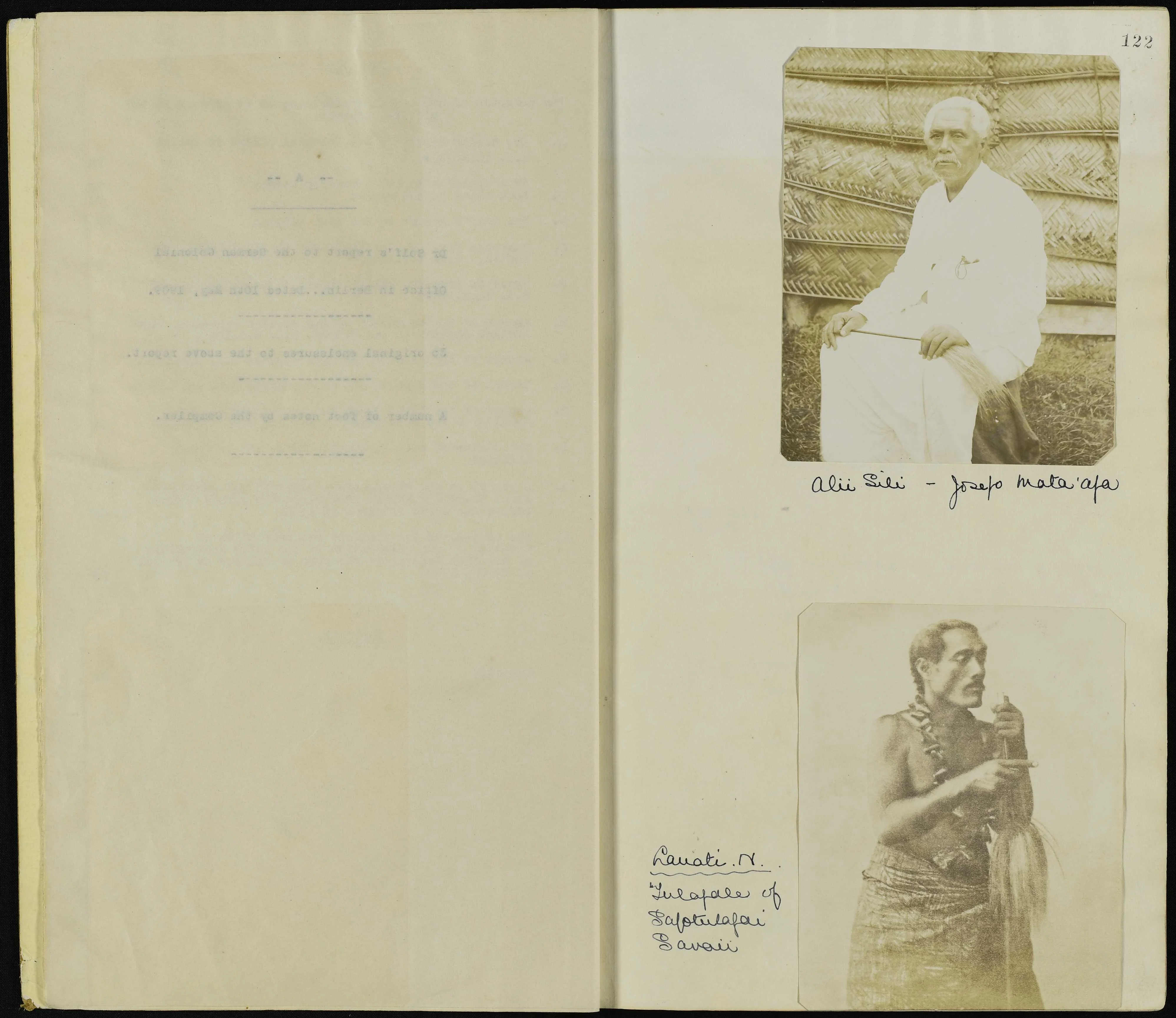

A Documentary Record and History of the Lauati Rebellion 1909 (O Le Mau Lauati), prepared by the Administration of Western Sāmoa.

ACGM 18974 R9498635

The bottom image shows Lauaki Namulau'ulu Mamoe. The top shows Sāmoan chief Ali’I Sili, Mata’afa Iosefo. They're taken from File 5 in the "Documentary Record".

Find out more about Mata'afa Iosefa - natlib.govt.nz

Mamoe gained some traction as leader of the Mau a Pule, until Governor Solf exiled him and 71 other members to faraway Saipan in 1909, as punishment for refusing to give up their opposition.

This image is File 35 in the "Documentary Record".

Next comes New Zealand – the Mau gains momentum

At the start of World War 1, Sāmoa swapped one coloniser for another. On behalf of the British Empire, New Zealand seized Western Sāmoa from the Germans in 1914. To begin with, little changed – the political and economic systems established by the Germans were largely maintained, but less strictly enforced.

But in 1918, New Zealand allowed a sailing ship carrying influenza to dock, setting in motion what was later described by the United Nations as one of the most disastrous and avoidable epidemics of the century. Left to fend for themselves by the New Zealand administration, 8500 Sāmoans died – including whole families, buried in mass graves.

This disaster became the foundation on which other grievances against colonial rule would be laid, reigniting the Mau independence movement – this time under the leadership of Olaf Frederick Nelson.

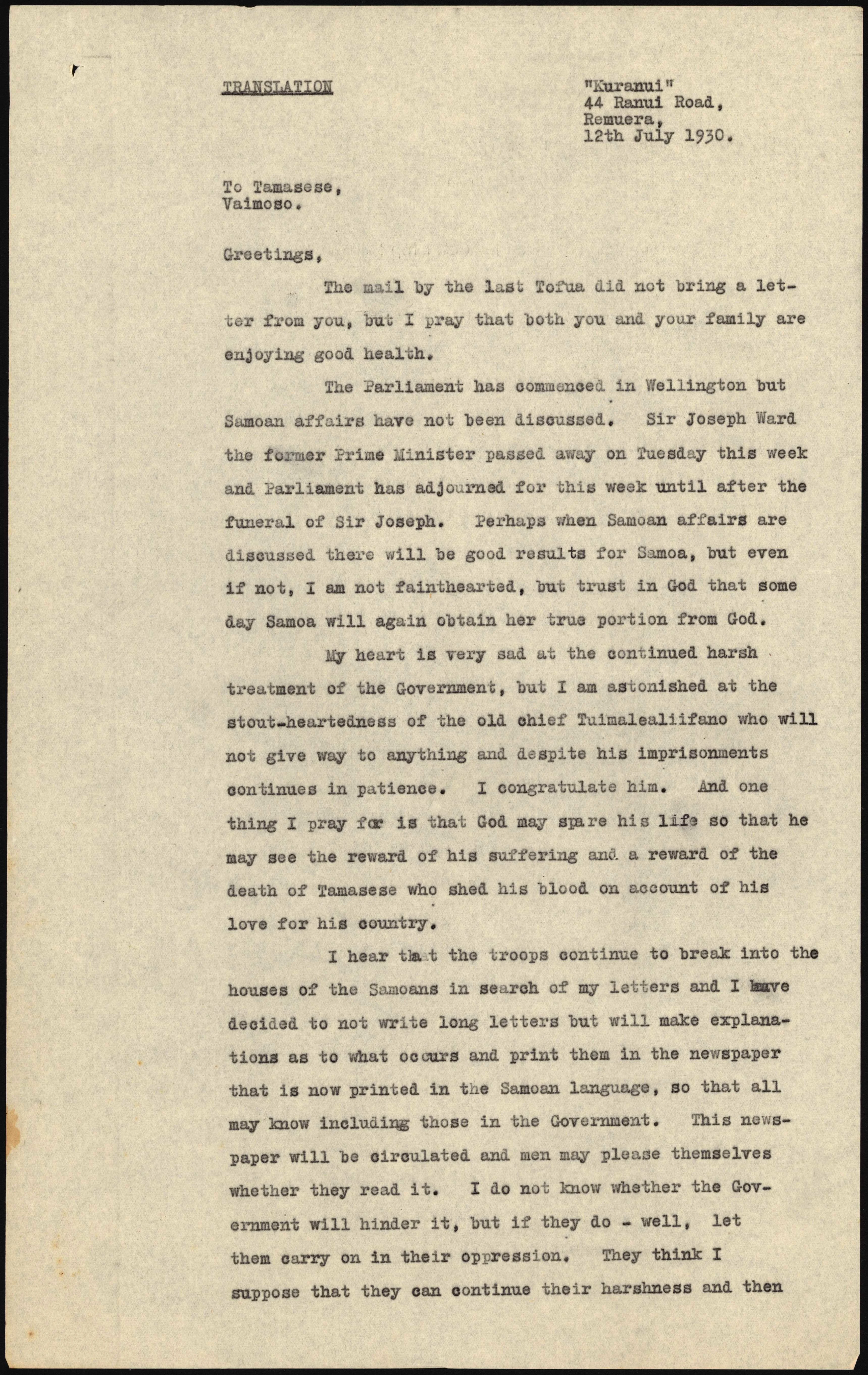

An influential Sāmoan nationalist and businessman, Nelson visited Wellington in 1926 to voice his grievances with the New Zealand’s government’s efforts to control Sāmoa’s copra market and the poor treatment of Sāmoans under colonial rule. When his complaints received no response, Nelson founded the second iteration of the Mau at his offices in Apia, with the slogan ‘Sāmoa Mo Sāmoa’ (Sāmoa for Sāmoans).

Sāmoa Mo Sāmoa – strength against oppression

This time, resistance made the Mau stronger. District councils and committees established by the administration were ignored, children were pulled from government schools. Labourers stopped going to work in the coconut and banana plantations. Instead of paying taxes, Sāmoans gave money to the Mau.

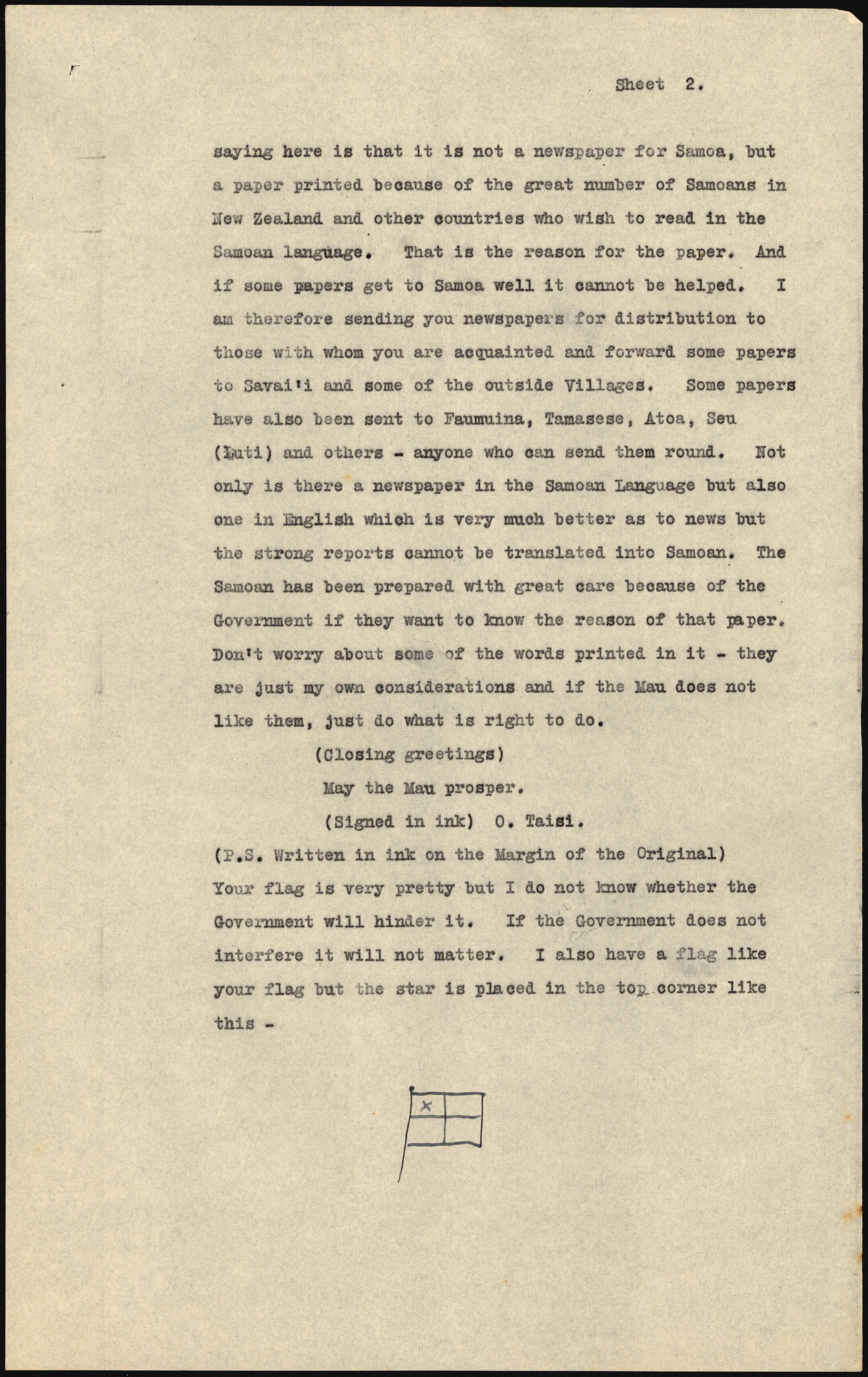

This intensified official disapproval and in January 1928 Nelson was deported from Sāmoa to New Zealand for five years, where he continued to push the Mau’s cause through mass meetings and the establishment of the New Zealand Samoa Guardian newspaper. After returning to Sāmoa in 1933, Nelson was exiled again the next year, for 10 years – though this exile was later revoked.

We hold exhibits, papers and judgements from Nelson’s court cases, brought together for his 1934 appeal in Wellington.

AAAR 24460 Exhibit 44 R23545268

Black Saturday – the darkest day in New Zealand-Sāmoa relations?

Meanwhile in Sāmoa, the Mau were intensifying their campaign under the leadership of Tupua Tamasese Lealofi III. It remained peaceful – European businesses were boycotted, Mau members turned themselves into police en masse to overwhelm the prison system.

The New Zealand administration responded with force, bringing in Royal Navy warships manned with marines to enforce laws banning Mau activities. After two violent confrontations between the police and the Mau in 1928, Tamasese was arrested for non-payment of taxes and imprisoned for six months.

The violence reached its peak on the morning of 28 December 1929 or Black Saturday, when Mau supporters, led by Tamasese, marched on Apia to welcome two Mau members who were returning from exile. As the peaceful crowd neared the courthouse, New Zealand police attempted arrests which the Mau resisted. The police were forced to retreat and fighting broke out, resulting in the death of a constable. Panicked New Zealand police fired rifles into the crowd, wounding 30 Sāmoans and killing 11, including Tamasese Lealofi III, who was trying to restrain the crowd when he was shot.

His death left a deep sense of grievance among many Sāmoans, exacerbated by the New Zealand administration’s response to Black Saturday, who adopted aggressive measures to ensure the Mau movement’s complete collapse.

It wasn’t until 1935, when the Labour Party came into power, that the Mau was recognised as a legitimate political organisation. It took another 67 years for a formal apology from the New Zealand Prime Minister, Helen Clark – to formally recognise and attempt to bring some closure to this little-known and uncomfortable chapter in New Zealand’s relationship with Sāmoa.