Ngā wāhine kei ngā pūranga - ngā reo o mua e whakaatu ana i ā rātau kōrero whakaaroha

Women in the archives — early voices tell poignant stories

Principal advisor Stefanie Lash reflects on how ordinary women appear — and don’t appear — in the government record.

On International Women’s Day, we reflect on the global achievements of women, our place in society, and the evolution of our right which were hard-won by women who came before us.

I am an archivist working with the government record at Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga Archives New Zealand. While I too celebrate the extraordinary women whose work is remembered by history, I have a special interest in ordinary women and how they appear — and don’t appear — in the government record.

Women and stories about them appear in some of the earliest government records. But their voices are absent, and they are discussed by men.

An anecdote I often think of is contained in an 1834 note dashed off by Hēmi Kepa Tupe, a rangatira (Māori chief) of Whangaroa in Te Tai Tokerau, who is writing to James Busby, British Resident, and Henry Williams, head of the Anglican mission. He relates a story of giving a man and a woman a lift in his waka to Matauri, and finding out later that they were eloping.

This might be the same woman who is referred to in an earlier letter from a ship’s captain, in which Busby is asked what he can do about 'a female slave' from Whangaroa. If she returns to her home, she will be killed. I often think of this unnamed woman, hope that she found safety, and reflect on her appearance in an early letter in te reo Māori — a tiny window into her life that we can read about 200 years later.

Some of the earliest records in which women speak for themselves are requests for relief to the early colonial government in Auckland. Before the welfare state and the benevolent societies that were established to provide for the destitute, women who had fallen on hard times had to appeal directly to the government for assistance. I find these stories give a fascinating 'history from below' view into the lives of women and children, and Victorian thinking about charity.

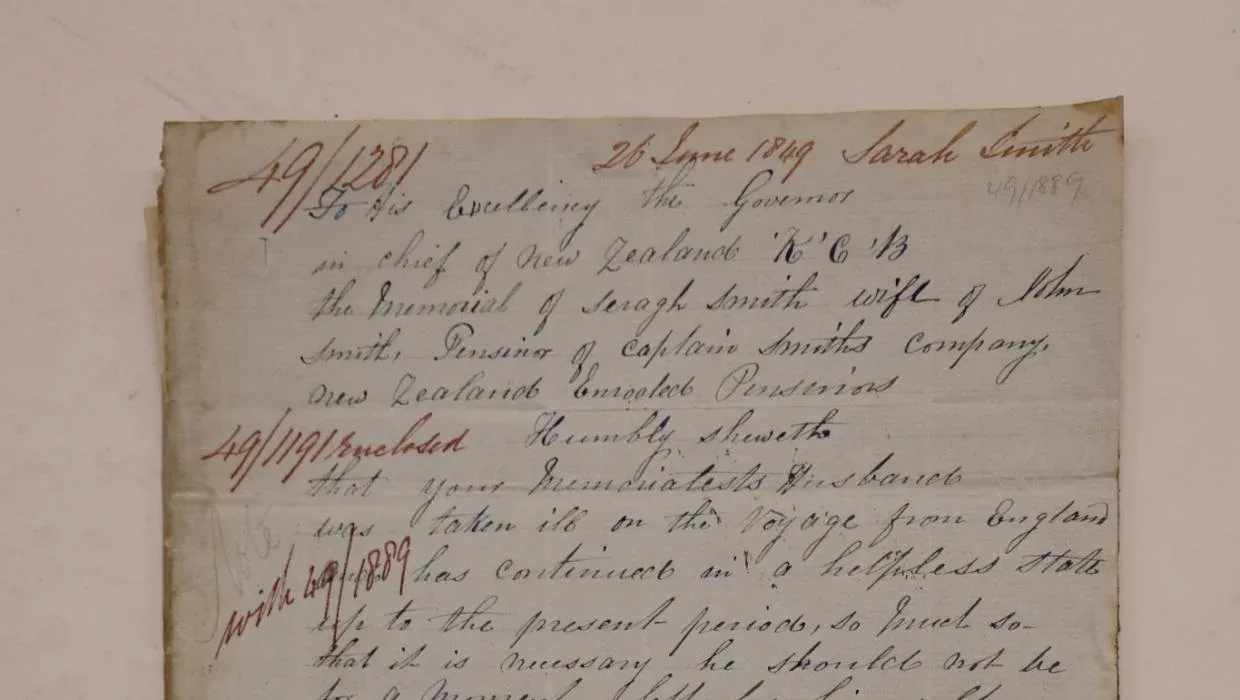

In June 1849, Seragh Smith from Howick wrote a petition directly to the Governor George Grey. She related that her husband had been ill for several months since suffering a paralytic attack on the voyage from England and asked 'that the destitute condition of herself and husband may meet with the kind consideration of Your Excellency'.

Officials decided that Seragh’s husband should be admitted to hospital and that she should receive half of his military pension of 16 pence a day — but not before observing that she was 'an indifferent character', meaning they thought she was of dubious morality.

Martha Duff from Parnell wrote to the government in 1850 requesting relief, saying 'one year ago we were, if not affluent, at least comfortable and independent' but that her husband had lost his business, 'rendering us sadly insolvent'. In an effort to recoup some losses he had gone to California, 'leaving me in the meantime with 4 little children, myself in delicate health, without the necessities of life'.

As with Seragh Smith, Mrs Duff’s character was investigated. The local Anglican reverend gave her a glowing character reference and a decision was made to grant her rations and an allowance.

In 1850s colonial Aotearoa, women’s property rights, women’s suffrage, the welfare state and the establishment of just working conditions for women were decades in the future. We can use public records to understand some small parts of the stories of the struggles of everyday women and their families in male-dominated public life.

The 1893 Women’s Suffrage Petition features at the He Tohu exhibition at Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa National Library in Wellington. Entry to the exhibition is free.